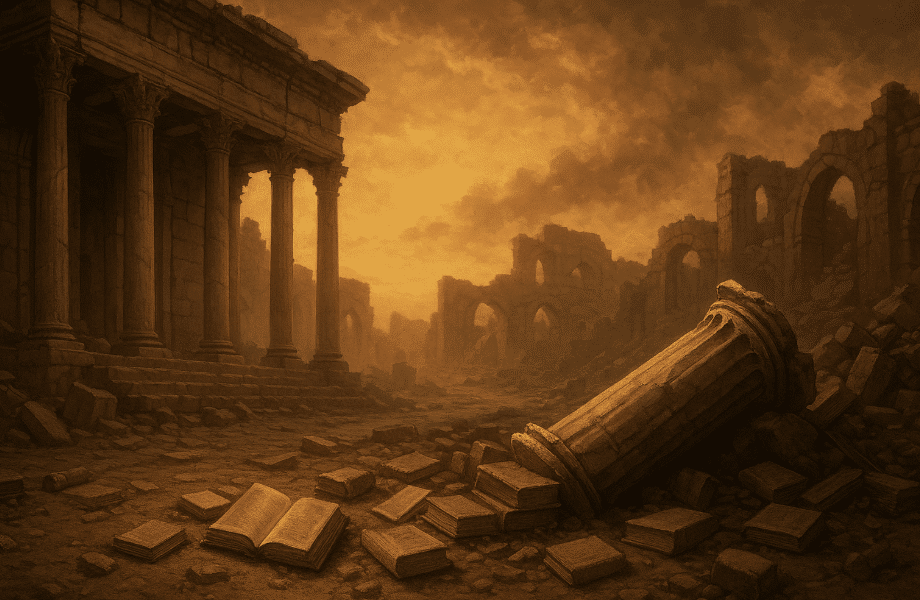

The Fire of Alexandria’s Library: Did Christians Destroy Ancient Knowledge?

Source: GreekReporter.com

Whenever someone brings up the Fire of the Library of Alexandria, misconceptions and historical myths take center stage. Not because people are willing to lie about such a monumental event in human history—quite the opposite. The problem is that almost everything people think they know about this topic is probably wrong.

The prevailing story is that Christian fanatics stormed Alexandria’s great library, burned everything to the ground, and therefore plunged Europe and the world into the Dark Ages.

This is a catchy story, to be honest. It has all the drama one might want to see in a historical event of such great proportions: religious zealots versus enlightened men, books going up in flames, civilisation collapsing overnight because of this confrontation.

Except it didn’t happen like that. At all.

What archaeologists and historians believe is quite different. What has been discovered over the years was far more complex and genuinely more depressing than the quick Hollywood version most of us are aware of.

The Great Library didn’t burn in a single dramatic night. It just… faded away, as so many things do when nobody cares enough to keep them going.

The Library of Alexandria

The Library of Alexandria, one of the most renowned centers of learning in the ancient world, was founded in the early 3rd century BC during the reign of Ptolemy I Soter, a former general of Alexander the Great and the founder of the Ptolemaic dynasty in Egypt.

It was likely his son, Ptolemy II Philadelphus, who brought the vision to full realization by commissioning the construction of the library as part of a larger institution known as the Mouseion—a temple dedicated to the Muses, the Greek goddesses of the arts and sciences.

Located in the city of Alexandria, the library aimed to collect all the knowledge of the known world and is believed to have held hundreds of thousands of scrolls covering subjects ranging from astronomy and mathematics to literature, medicine, and philosophy. Scholars from across the Mediterranean were invited to study and translate texts, making the library a symbol of intellectual ambition and cross-cultural exchange in the Hellenistic era.

Why the belief in the Fire of the Library of Alexandria exists

This whole confusion started with Edward Gibbon back in the 1700s. Gibbon had some issues with Christianity and needed someone to blame for Rome’s collapse, like any good historian would do. The narrative of Christian book-burners fit his version of history perfectly. Then Carl Sagan picked up the story for his TV series “Cosmos” centuries later, and suddenly half the world believed they had watched ancient knowledge go up in smoke because of a handful of religious fundamentalists.

However, when you read the ancient sources without cherry-picking quotes, they tell a completely different story.

Take Ammianus Marcellinus, who was writing about Alexandria in the 4th century. He mentions the library, but he’s more concerned with political upheavals and economic problems. It’s the same with Socrates Scholasticus, who actually lived through some of these events. Neither of them describes anything like the dramatic destruction modern writers love to imagine.

The real problem is that we are used to simple stories. Good guys versus bad guys. A clear moment when everything went wrong. But history doesn’t work like that, especially not institutional history. Libraries don’t just disappear overnight unless there’s an earthquake or a natural disaster. They decline gradually as funding dries up, staff leave, collections deteriorate, and society discovers other interests.

This is not new. It also happens to modern institutions. Think about the small-town library where people spent their childhoods. It didn’t stop being around because religious fanatics burned it down. It was because the local government cut funding, people stopped borrowing books, and nobody could be bothered to fight for it anymore. This is how most institutions die.

The Ptolemaic library system had been struggling for centuries before Christianity arrived on the scene. Political chaos, reduced patronage (meaning reduced funding), and competition from other centers of learning—all the usual suspects—were already contributing to the demise of the Library of Alexandria.

What the sources tell

So what really happened? Well, there were several incidents, spread across different centuries, and none of them match the popular story.

The largest documented fire occurred in 48 BC, and it was Julius Caesar’s fault. His fleet caught fire in Alexandria’s harbor, and the flames spread to dockside warehouses stuffed with papyrus scrolls. Thousands of texts must have been lost during this accidental fire. It was a genuine disaster, but these were commercial copies waiting to be shipped elsewhere, not the main library collection.

Many decades later, Alexandria experienced a revolt during the reign of Emperor Aurelian in 272 AD. The whole city sustained severe damage during the fighting. Dio Cassius mentions buildings were destroyed, quite possibly including parts of the library complex. Again, this was war damage, not targeted destruction of knowledge.

Now we get to the part everyone argues about.

In 391 AD, Archbishop Theophilus did order the destruction of the Serapeum. This was a temple complex that housed some scrolls and served as a meeting place for pagan intellectuals. Christian mobs were involved, and it was violent and ugly. Some knowledge was lost during that incident.

It is crucial to note that contemporary Christian writers such as Rufinus and Sozomen, whom one might expect to boast about destroying pagan learning that conflicted with the teachings of the Church, don’t even mention books being burned. They focus on smashing statues and stopping pagan rituals. If there had been a massive book-burning incident, surely someone would have bragged about it…

Hypatia’s murder in 415 AD was another genuinely horrific event in Alexandria and represented a real loss to intellectual life. But she wasn’t connected to the ancient library. She ran her philosophical school and was embroiled in heated local politics between the prefect, Orestes, and the Patriarch, Cyril.

What emerges from all this is a steady institutional decline, not a single event of dramatic destruction of the Library of Alexandria. The library system could not adapt to Roman rule, Christian culture, and changing educational priorities, all of which contributed to the swift change in the priorities of the Alexandrian society. It’s quite boring compared to the myth.

Yes, Christians destroyed many pagan temples, art, and even books in the 2000 years of their presence in the world. But Christians also preserved more ancient texts than they destroyed, and the evidence is overwhelming.

Medieval monks dedicated centuries to copying everything they could access, particularly works by ancient Greek writers. They preserved pagan philosophy, romantic poetry, medical treatises, and astronomical observations. Often, they did so without fully understanding the content, simply because they believed it might be important for future study.

An excellent example is the monk who copied Ovid’s “Art of Love”—essentially a playful Roman guide on how to win over women—and added marginal notes attempting to interpret it as a Christian allegory. Clearly, he didn’t understand what he was copying, yet he proceeded to do so anyway.

When Muslims conquered Alexandria in 641 AD, they didn’t burn the remaining libraries. They translated everything they could find. Greek mathematics, philosophy, and science all got preserved in Arabic. Some classical works still exist today because Islamic scholars recognized their value and preserved them.

This doesn’t mean all Christians loved pagan learning. Some church fathers were genuinely hostile to classical culture because of their fundamental perception of the Christian faith.

The original article: belongs to GreekReporter.com .