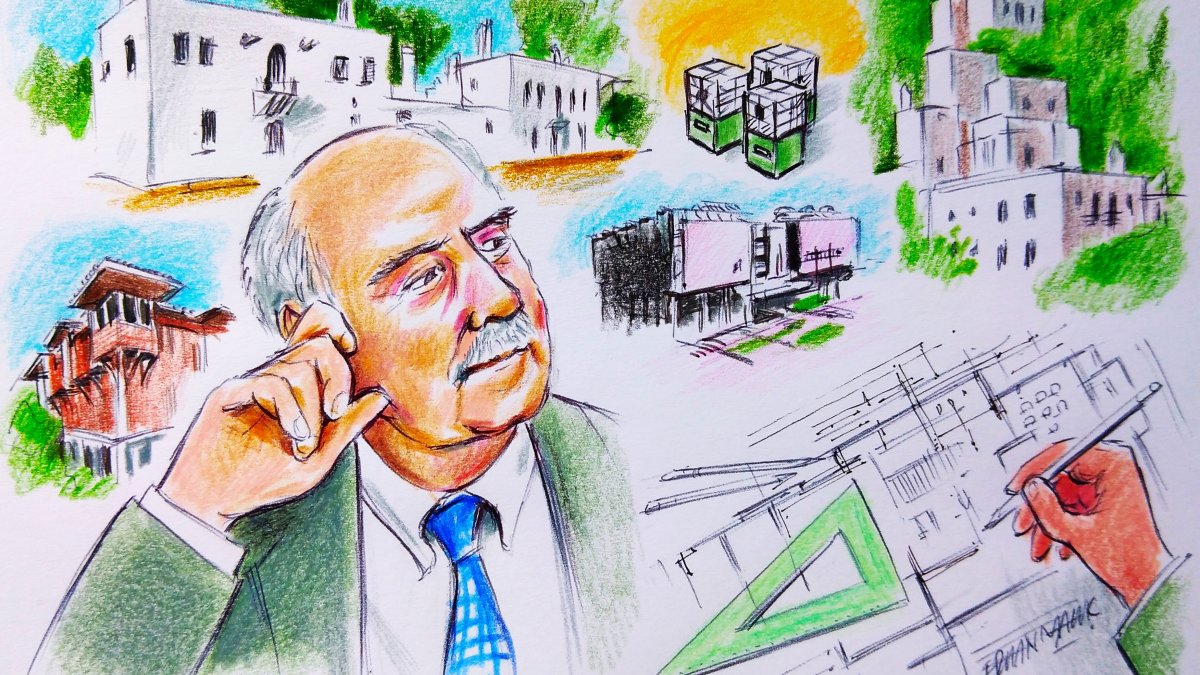

Turgut Cansever and the reinforcement of the public human

Source: DAILYSABAH

Turgut Cansever was an architect in Türkiye who placed the human being at the center of design and sought to build the relationship between architecture and people. He consistently emphasized the importance of the relationship between buildings and lived life, valuing respect for scale, beauty, coherent dynamism and integrity among structures. He particularly stressed that these dynamics must serve as focal points in the development of new cities. This article, taking as its center Cansever’s book “Home and City” (“Ev ve Şehir”), examines the systemic unity underlying his perspective on the house and the city.

An architectural perspective structures not only the human being at its core, but also human relations, the environment, family life, and social and economic existence according to a system of values. When any building is evaluated together with its surroundings, it becomes possible to see in detail which values it seeks to preserve. Throughout his life, what Cansever emphasized was that architecture must present an integrity as a reflection of the system of values. In the past, when this integrity was preserved and dominated the cities, the transformation that began in architecture actually corresponded to a transformation within the system of values. Ignoring this fact led to Cansever’s outcry, as he was the lone voice proclaiming that what was lost was this perspective of integrity/unity (tawhid), and that the social cost of such a loss would be exceedingly high.

Wholeness is directly related to the conception of existence. Therefore, architecture that springs from this essence must also take into account the integrity of existence. From an Islamic perspective, the fact that the human being is a noble existence and that the world should be beautified in parallel with this holds central importance. According to Cansever, architecture, being an art that organizes all realms of existence, is not a worldly process detached from morality. On the contrary, it is a body of actions that contains and reflects the system of values shaping life. Within this framework, tradition and culture are formed, and tradition, enriched over time, acquires a historical accumulation. This accumulation, in turn, facilitates the resolution of new problems that arise. Hence, as Turkish architect Halil İbrahim Düzenli states, “Cansever’s world of thought, or conceptual framework, begins with inquiry into the realm of existence, continues with the understanding of historical experience, and is rendered contemporary through the search for solutions specific to geography.”

Scale, network, collapse

In Cansever’s perspective, just as “individuality” and “beauty” hold central importance, so too does the relationship of individuality with its surroundings. Even his short article titled “Beyazıt Square,” written in 1961, is sufficient to grasp his concern. In it, he discusses the differences between the condition of Beyazıt Square of Istanbul in 1961 and its past texture, grounding his analysis in the divergences of sensibilities underlying the process. He states very clearly that the square – which once maximized the relationship between human beings and their environment – was rendered incapable of fulfilling its functions due to newly constructed buildings that disregarded scale and the meaning of the square’s center, and particularly because of roads opened to traffic.

There is a powerful interaction between human beings and buildings, one that directly influences the individual. The architecture of an urban fabric, in fact, directly shapes the network of connections between people through their relationship with buildings. When one looks at a given fabric, it is possible to discern – through the network of relations it generates – what that fabric makes possible and what it renders impossible. The structure of the network also determines the scope of human relations. Moreover, within this network of relations, it also becomes clear which building or buildings will hold the center. Thus, an architectural composition inherently contains a vision of what kind of human life it foresees. As Turkish scholar Ihsan Fazlıoğlu expresses it, the architect, being “a poet who interprets space,” carries out this interpretation on the basis of culture’s conception of “God-Cosmos-Human” and their relations: “As a universal (külli), it too becomes a representation of the Universal, that is, of the Cosmos, through the architect’s intentionality – his knowledge and learning – being infused into space. In this way, like the Cosmos, which signifies God, essences/universals – that is, concepts – intertwine with the space-time relation to form a web. Undoubtedly, this web is a representation that embodies the culture’s conception of and relations between God, the Cosmos, and the Human: a theo-ontology.”

In the context of Beyazıt Square in Istanbul, Cansever emphasizes the importance of this network structure. What Cansever points out regarding Beyazıt Square is that the integrity of the focal point with its surroundings has been disrupted in this way, thereby rendering the focal point incapable of fulfilling its function. Cansever particularly stresses that this transformation began with the Tanzimat period. In fact, this fabric that is intended to be created and sustained in architecture exists in nearly all civilizations. While a sacred structure forms the focal point, the square and modest houses take their places around this center in a respectful scale, and everything revolves around it. Late Turkish philosopher Teoman Duralı provides a similar example for Greek civilization: “As we said, the houses are very modest. Public buildings are extraordinarily beautiful. Not much is done for individuals, but the public building, the temples, the state buildings are magnificent. The Greek city is circular in form. The circle is considered sacred. At the center of this circle lies a great square. This square is called the agora. Eighty percent of social life takes place in this agora. There, buying and selling occur, the affairs of the city are discussed, its laws debated, conversations are held, friendships are nurtured, gossip is exchanged – everything happens there.”

The hierarchy between the center of the fabric and its surroundings is likewise structured according to a scale, creating an illusion based on the idea of relative magnitude. In other words, there exists an implicit order of scale within the city. The focal points connect, in particular, the neighborhood and, more broadly, the entire city as a whole. The inhabitants of the city, by showing respect for the prevailing scale of the city, participate actively in its processes, and by constructing buildings that are harmonious and respectful toward the focal structures and the surrounding fabric, they expand this integrity with a fluidity that takes scale into account. In this way, each addition reconstructs the whole, ensuring that beauty is not disrupted by these extensions.

The awareness of an open-ended/developing integrity formed around the focal point is kept alive among the city’s inhabitants. In this way, neighborhood residents continuously develop their capacity to solve problems within the neighborhood by actively participating in all of its processes. This participation enriches the individual through a broad sense of duty and responsibility – ranging from cleanliness and security in the neighborhood to neighborly relations and even intervention against structures that would disrupt this integrity. In short, within this climate, people are able to engage actively in processes with a sensitivity toward their environment.

In his book “The Fall of Public Man,” American sociologist Richard Sennett draws attention to the importance of architecture in the loss of the human being’s capacity to engage with their environment and participate in processes. According to Sennett, the new architectural approach “involves a far more perverse idea, such as the destruction of lively public spaces and making space dependent on movement.” Architectural designs in such contexts center movement rather than encouraging people to stop and interact. Consequently, human beings are forced to move rapidly through these spaces in accordance with this design. Thus, people can no longer truly exist in the street, the neighborhood, or the square; they merely pass through. Nor can they feel a sense of responsibility toward what they pass by. In this way, individuals become alienated from their surroundings: “The logic of the Defense Department or Lever House plans is compatible with transport technologies precisely in this regard. In both cases, as public space becomes a function of movement, it loses its meaning as an independent experience of its own.”

Rent and loss

With the Tanzimat period, the dynamics and characteristics of the city were completely overturned. The focal point shifted. The city’s order of scale was utterly destroyed, and the foundations of rent-seeking began to be laid. Not only was the consciousness of wholeness in the cities shattered, but at the same time people’s participation in processes was eliminated, thereby weakening the strong relationship they once maintained with their environment. As a result, this attitude pushed the mosque and its cultural axis outside the sphere of lived space. On the other hand, the individual – who had once been active in shaping the traditional house structure and bore responsibility both for the home and the neighborhood – was severed from this active process of participation through the advent of apartment living, and was condemned first to passivity, then to individualistic indifference, and ultimately to alienation.

The new formation is not merely a partial transformation in construction; on the contrary, it signifies a radical rupture from the system of values. Once the sensitivity of the scale that connects structures to one another is disrupted, the vacuum is inevitably filled by rent. Thus, concentrations begin to emerge in the city. In areas of such concentration, the path is opened for legitimizing value increases that raise individual rent but are secured through public resources. For this reason, Cansever does not regard this transformation solely as an architectural collapse, but also relates it to a moral collapse.

One of the roots of the problematic that late Turkish thinker and author Alev Alatlı points to – how the legal and the permissible (halal) can overlap – was in fact initiated by this transfer of rent. Indeed, at the very beginning of his book, on the first page of his 1993 article titled “Planning Istanbul on a National Scale,” Cansever proposed a way to eliminate this distinction: “Making it impossible for the legal structure to embody any morally corrupting or speculative factors.” When the participation and capacity for intervention (responsibility) of the people living around a plot of land are eliminated, the vacuum is filled by central bureaucrats, and the process of corruption begins. Thus, the door is opened to the production of legal rents that are not, however, halal. In other words, with this door open, the necessity for what is legal to also be permissible/moral is abolished. The new network of relations now sustains an entirely different set of values.

The original article: belongs to DAILYSABAH .