From Hydra to the Hunter: The Hydriot Pirate who rewrote an Australian family’s story

Source: NEOS KOSMOS

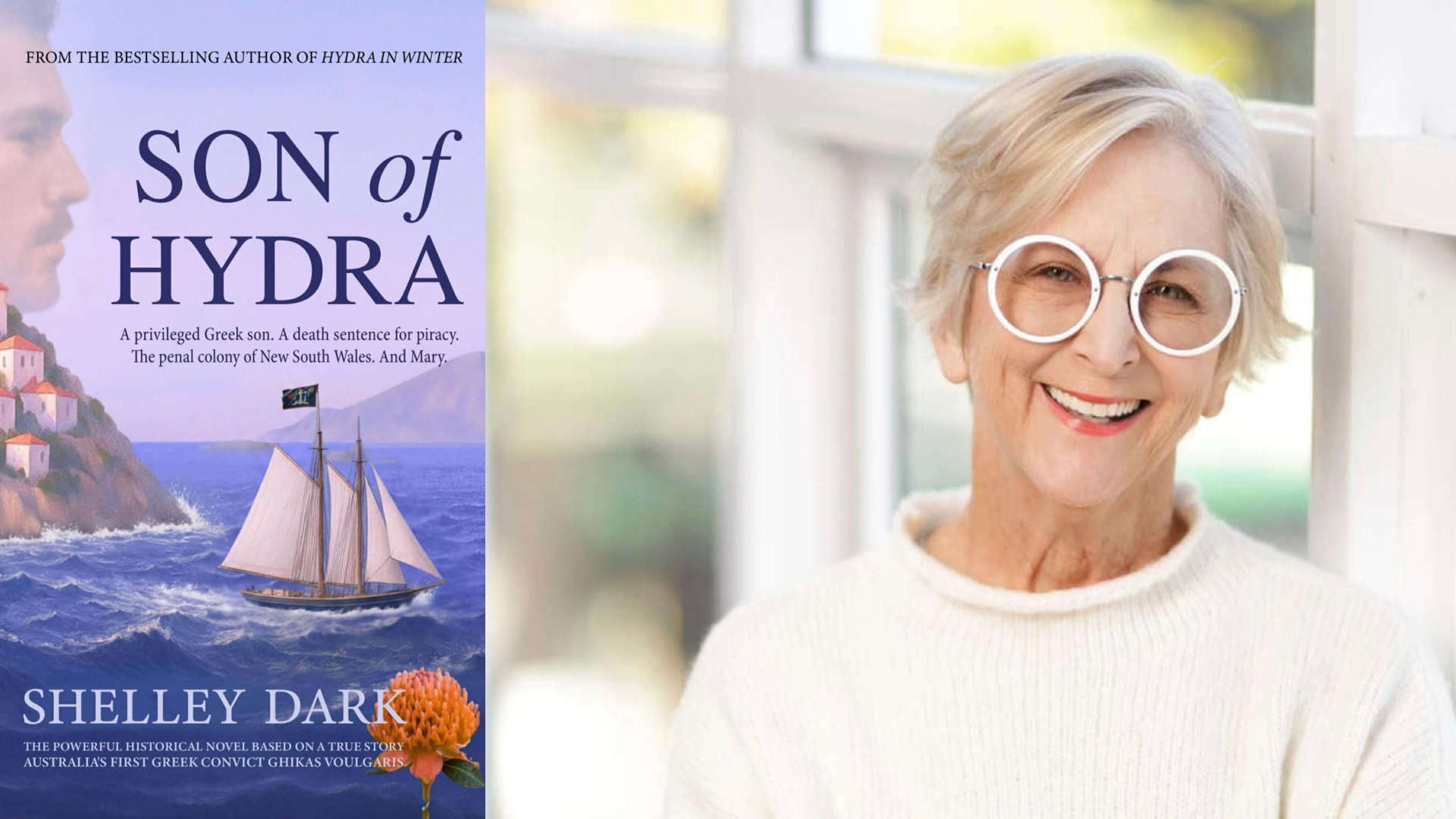

Years into her marriage, Queensland-based author Shelley Dark learned that her husband was the great-great-grandson of a Hydriot pirate. At first, she thought she’d misheard. Pirates belong in swashbuckling adventure stories for kids, Hollywood films, pr headlines about modern piracy, not family trees. The revelation sent her into a deep-dive into the world of Ghikas Voulgaris, Australia’s first recorded Greek convict who became the beating heart of her Dark’s new novel ‘Son of Hydra’.

“For most of us, pirates belong either in children’s stories or in modern headlines about violence on the high seas,” she tells Neos Kosmos.

“So to discover, quite late in my marriage, that my husband was the great-great-grandson of one was, honestly, totally shocking.”

What began as curiosity quickly grew into something else. Dark wanted to know who Ghikas was – his parents, his world, and what pushed him towards the sea and into the hands of the British.

“At first, that was all I wanted to know. But the more I found out, the more I wanted to know.”

She had no idea then just how large his world really was nor how much of it she would eventually walk.

Following Ghikas across seas and centuries

Dark’s research took her far beyond the desk – she went to Hydra, Malta, Portsmouth, Cork, London, and New South Wales. The same journey Voulgaris took under vastly different circumstances. Those landscapes shape not just the historical backbone of the novel, and provide it a backdrop for its emotional depth.

“The physical reality of travel gave me the facts I could never access online,” she says. “But being in the actual places… supplied the texture. The thickness of walls and sills, the quality of light, the air in an underground cell.”

The emotional knowledge, however, arrived in unexpected waves.

“Looking down over Hydra and feeling, unexpectedly, the shock of leaving home forever… Standing in a Maltese cell and feeling claustrophobia rise in my chest… Sitting under a tree at Arnprior where he and Mary may have sat, sensing the excitement of a love affair beginning.”

These moments, she says, “weren’t research; they were visceral.”

A Greek outsider in colonial Australia

‘Son of Hydra’ is told entirely in Ghikas’ voice. Wry, proud, wounded, and deeply human.

Crafting the perspective of a Hydriot aristocratic youth in the harsh early colony resisted stereotypes of both Greeks and convicts and for Dark, this came naturally.

Voulgaris himself defied every cliché.

“He wasn’t a poor pickpocket of English stock but a privileged young man from a well-known Hydriot family, and he was a pirate. That alone knocks him outside any neat category.”

Nor did she allow the colonial setting to drift into romanticism.

“There’s nothing romantic about having your ankles chained together,” she says.

“And I lived my whole working life on a farm, so I know what real work feels like. I couldn’t pretend exhaustion, heat, hunger or injury were poetic.”

Instead, she leaned into the contradictions that define people across eras.

“People haven’t changed since Aristotle’s day. They’ve always been complicated, contradictory, stubborn, loving, foolish. I wanted each character to be an individual, not a symbol.”

A love story cut across cultures

At the centre of Son of Hydra sits the unexpected love between Ghikas and Mary Lyons, a teenage Irish orphan who made the perilous journey across vast oceans alone. Their marriage, historically true, defied every assumption of their worlds.

“The idea that he met and married a penniless Irish orphan… is astonishing,” Dark says. “And yet they did marry.”

Mary, as she imagined her, is no passive colonial girl. “Forthright, intelligent, wary, and absolutely unwilling to be diminished,” she became a counterpoint to Ghikas’ rigid expectations.

The novel explores the tension and possibility of two young people forging something real despite culture, class, and fate.

“How do two people reconcile wildly different cultures when they fall in love?” Dark asks. The novel’s answer is neither idealised nor despairing, but grounded in character and choice.

Brotherhood, loyalty, and the fierce bonds between Hydriot men pulse through the narrative.

For Dark, these relationships were essential, not only to Ghikas, but to the modern Greek diaspora.

“On Hydra those friendships were sharpened by history: boys working at sea, relying on each other in dangerous conditions… shaped by pride, rivalry and responsibility.”

For a shipowner’s son, syntrofikotita, that deep companionship, was instinctive.

“When everything else was stripped away, that duty to his friends was the one part of himself that still propelled him.”

Dark hopes contemporary readers, especially Greeks in Australia, will recognise these dynamics immediately: the humour, the protectiveness, the sharp tongue and lifelong loyalty.

Reframing Greek Australian history

While her earlier, ‘Hydra in Winter’ resonated with diaspora audiences, ‘Son of Hydra’ navigates deeper historical terrain. Dark wants readers to reconsider the familiar timeline of Greek migration.

“Greek migration to Australia is usually imagined as a twentieth-century story,” she says.

“What I hope Son of Hydra offers is a reminder that the Greek presence here began far earlier, and under far harsher circumstances.”

These young Hydriots, transported convicts, have been largely erased from historical memory, she argues. Returning them to the narrative broadens the story of who the first Greeks were, and how they endured.

“I hope the novel gives an accessible doorway to those who read only in English, so this part of their history isn’t lost to them.”

It is a story about identity, how it fractures, and what it inherits, as well as, its ongoing negotiations.

“Ghikas’ life touches on questions that still matter: what is carried from the old world, what is shed, what is rebuilt… and how Greeks maintain their cultural heritage while embracing their new Australian identity.”

Son of Hydra has drawn comparisons to works such as The Light Between Oceans and The Narrow Road to the Deep North, with readers calling it ‘cinematic, heartfelt and meticulously researched’.

Praise from prominent writers such as Dean Kalimniou, Yvette Manessis Corporon and Peter Barber underscores the significance of the story Dark is reclaiming.

Set against the backdrop of war-torn Hydra and the raw landscapes of early New South Wales, the novel asks one essential question. Will Ghikas try to reclaim the life he lost, or build a new one with Mary?

In telling his story, Dark has restored a vital, missing thread of Greek Australian history—one that was nearly lost to silence.

The original article: belongs to NEOS KOSMOS .