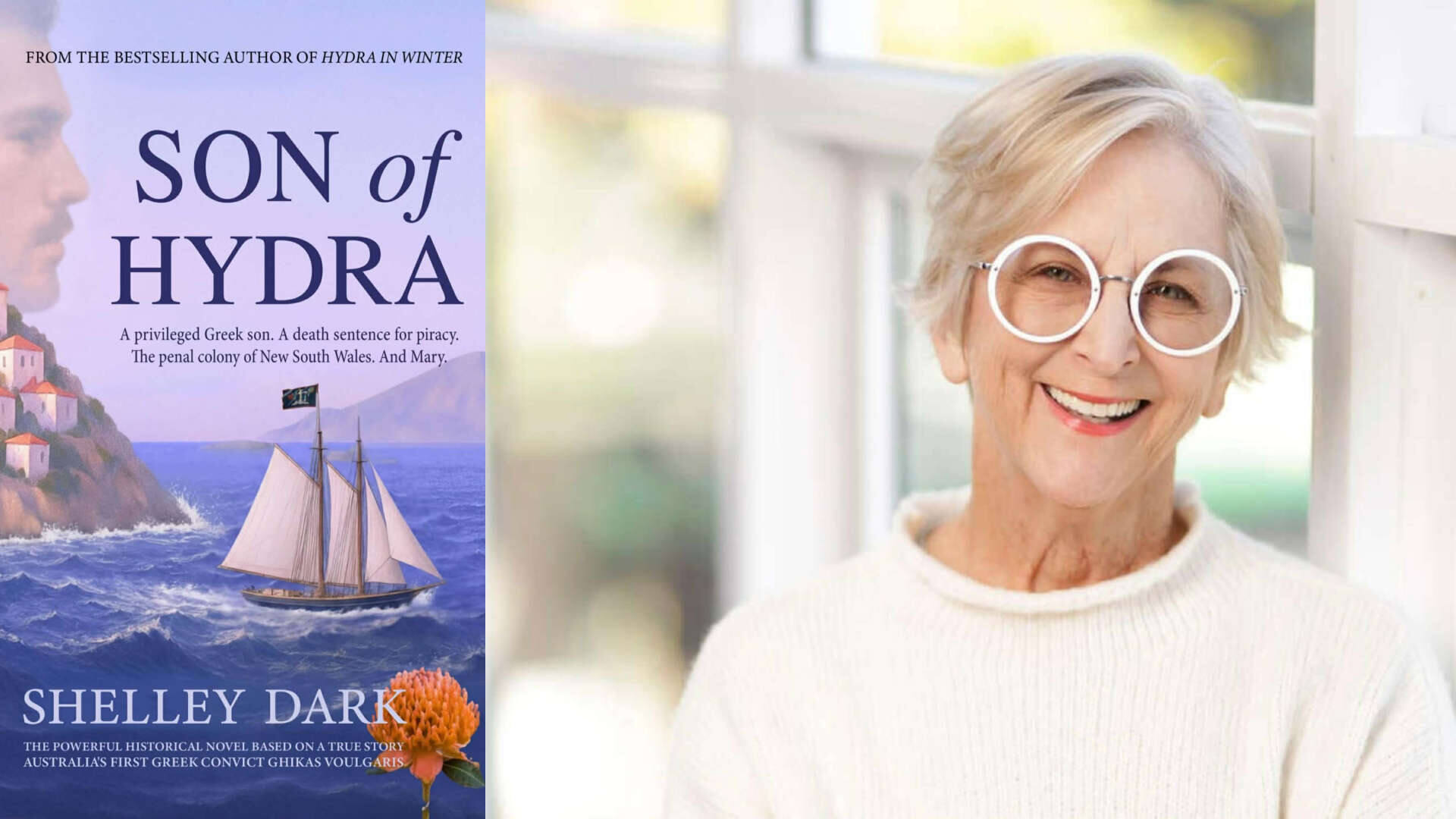

Diatribe: Son of Hydra

Source: NEOS KOSMOS

Shelley Dark’s new book: Son of Hydra moves like saltwater through the consciousness of every Greek-Australian who has ever reflected upon the history of their forefathers. The narrative begins in exile, and the reader is immediately placed within the salt-stained boots of Ghikas Voulgaris, a young Hydriot who once stood at the threshold of inheritance, maritime command and familial expectation. Circumstance transports him instead upon the convict ships of Empire, the outcome of imperial suspicion and the harsh logic of history. We embark beside him, caught within opposing currents. The embers of the Greek Revolution continue to glow, while the British sentence passed upon him casts a long shadow over his identity, tinging his courage with doubt and marking him as both defiant and compromised.

Dark’s masterly portrayal of companionship is one of the novel’s most affecting achievements. Ghikas’ four compatriots, Andonis, Damos, Kostas and Nikos, travel beside him, each shaped by distinctly Hydriot sensibilities that transcend their island’s borders. Andonis possesses a gentleness that lends to every scene a quiet constancy. Damos, tough and irreverent, challenges authority and fate with the ease of one accustomed to hardship. Kostas, reticent yet unwavering, reveals a depth of character that is rooted in loyalty and inner strength. Nikos, the most exposed to harm, grounds the group’s humanity through his refusal to believe that cruelty must be repaid in kind, and through his yearning for the kindnesses of home. Dark renders their brotherhood with such intimacy, and with so faithful an ear for Hydriot idiom and interaction, that Hydra itself seems to pulse through their speech, gestures and glances.

Ghikas’ gradual transformation is charted with sensitivity and insight. He begins with the ardour of one raised amid revolution and maritime prosperity, imagining a future of command, wealth and social standing. As the story unfolds, he exchanges ambition for the more exacting demands of survival, resourcefulness and dignity. Leadership takes on new meaning within the penal colony. It ceases to be the art of strategy alone and becomes the work of protecting others, negotiating peril and at times enduring in silence. The memory of his father’s condemnation weighs heavily upon him, although the reader witnesses his slow ascent from shame. Every act of care towards Nikos, every negotiation with a guard, every flash of humour that defies despair contributes to his quiet reclamation of self.

Ghikas Voulgaris, among the earliest Greeks to set foot upon the Australian continent, serves as both mirror and lantern for generations of Greek-Australians seeking to understand the foundations of their presence here. Dark’s depiction compels attention because it defies simplistic categories. The narrative dwells in the unresolved space where legend meets record. The seven Hydriots, labelled pirates by some and hailed as freedom-fighters by others, are presented as men negotiating the shifting ground of imperial law, settler violence and the intricate politics of inheritance. The question of whether to embrace or obscure a convict genesis becomes emblematic of broader tensions within diasporic memory. British Imperial designation of piracy reveals itself as an act that imposes a legacy of transgression, binding newcomers to an Australian mythos born in violence and moral ambiguity.

Through a postcolonial lens, Dark’s narrative intervention becomes more than a literary exercise. It constitutes a critique of the coloniality of the archive and its epistemic violence. Ghikas is a subject historically positioned within structures that denied him narrative authority, recorded through British legal discourse that defined him through criminality and suspicion. His presence in the colonial record was shaped by institutional mechanisms that sought to categorise, discipline and silence the non-Anglo other. Dark’s act of fictional recuperation intervenes in this authorised narrative space by constructing a counter-archive in which Ghikas is endowed with interiority, agency and ideological complexity. This intervention is complicated by the author’s position as a member of the dominant cultural group within contemporary Australia, although this again is rendered ambiguous by her being married to a descendant of the historical Ghikas. The postcolonial ethical stakes of ventriloquising a subaltern voice must nonetheless be acknowledged.

While the subaltern may not speak within the colonial archive without mediation as Spivak would conend, Dark’s project rejects the simplistic restoration of voice common to rehabilitative historical fiction. She neither idealises Ghikas as a hero reclaimed from British slander nor reproduces the colonial caricature that reduced him to a disruptive foreign element. Instead, she sustains the tension inherent in subaltern representation. Ghikas is allowed to exist within contradiction, capable of courage and misjudgement, loyalty and anger. Dark’s marriage into the Voulgaris line further complicates this dynamic. She writes as both heir to the settler-colonial cultural centre and as custodian of a diasporic inheritance. This duality mitigates the risk of epistemic appropriation and situates her narrative labour within an ethics of relational accountability, rather than detached scholarly claim over the subaltern voice.

Such an approach avoids the triumphalist tendencies that have often characterised Greek and Greek-Australian retellings of foundational migrant narratives. In place of hagiography, Dark offers critical intimacy. The legacy of the seven Hydriots has often been filtered through a lens of heroic exceptionalism, in which the convict stain is erased, the men recast as proto-migrants whose presence foreshadowed the industriousness and moral fibre of later Greek arrivals. Dark resists this narrative sanitisation. Her novel exposes the discomforts of diasporic belonging, revealing that the desire to mythologise origins is itself a response to the anxieties of minority identity negotiation within a settler-colonial society. By reintroducing complexity and moral ambiguity into the story, she challenges communities to confront the shadowed dimensions of their own past.

Among the secondary figures, Mary Lyons emerges with particular force. Frequently relegated in colonial narratives to the role of witness or reward, here she possesses agency, moral complexity and resolve. She declines the prospect of a circumscribed Greek womanhood defined by absence and instead attempts to fashion a life within the unsettled realm of the colony. Her relationship with Ghikas unsettles familiar binaries. Otherness is no longer simply the Greeks in conflict with British power, for both characters must confront their own dislocation, longing and limits of adaptation. Dark’s perceptive handling of gender, power and the hidden migrations of shame across cultures grants the novel a rare depth.

The novel also offers a gentle reframing of women’s place within such origin stories. Dark accords Mary Lyons a degree of presence and inner life that counters the erasures which often afflict women in both colonial and diasporic narratives. Rather than functioning as a sentimental ornament to the male exile or a moral yardstick against which his character is measured, Mary is allowed a voice, a history and a personal reckoning with the limitations imposed upon her. Her choices are shaped by the social codes of the period, yet she retains a quiet determination to shape her life with dignity. Through Mary, Dark demonstrates that the experiences of women in the colony possessed their own moral and emotional complexity, and that they too navigated profound displacement. In granting her such careful attention, Dark enables a more humane and inclusive retelling of the foundational story.

This treatment intersects with another element that distinguishes Son of Hydra from many Greek and Greek Australian accounts of early migrant figures. Diasporic retellings have often elevated the male pioneer to emblematic status, investing him with virtues intended to counteract insecurity in the host society. The cost of this narrative strategy is that the women connected to such figures are turned into abstractions. They are invoked as patient keepers of the hearth, as guardians of memory or as silent companions to the heroic male trajectory. Dark resists this pattern. She neither idealises Mary as a vessel of moral purity nor diminishes her as an appendage to Ghikas’ odyssey. Instead, she invites readers to recognise that women participated actively in the formation of community and in the bearing of its moral burdens. Mary’s endurance, integrity and capacity for compassion become essential to the preservation of the legacy that later generations inherit. In this sense, Dark subtly restores women to the narrative as agents of continuity rather than symbols of passivity.

The novel’s closing sections reinforce its central preoccupation with the formation of identity in conditions of rupture. The seven Hydriots come to embody the experience of forging meaning amid loss and reinvention. Their story resonates with those who have inherited the mixed legacy of migration, for it acknowledges that belonging is achieved gradually, through choices made in adversity, through acts of compassion and through the refusal to surrender one’s sense of self. Dark’s vivid prose, attentive characterisation and commitment to ethical storytelling combine to produce a work that honours the complexity of the past without succumbing to nostalgia or to triumphal myth-making.

There is a quiet courage in Dark’s method. She declines to resolve every contradiction or to claim moral certainty on behalf of her characters. Instead, she invites readers to reflect on the ambiguity that defines human lives. The seven Hydriots are neither purely heroic nor wholly compromised. They are men who endured displacement, injustice and the weight of expectation, who made mistakes and who sought redemption in small gestures of humanity. In presenting their story in this way, Dark encourages contemporary readers to approach their own histories with humility, curiosity and compassion. The legacy she articulates is one of complexity embraced rather than denied.

Son of Hydra may be read as an invitation to reconsider the narratives through which communities understand themselves. It suggests that dignity resides not in the perfection of origins, but in the willingness to confront them with honesty. For Greek Australians, this requires the courage to acknowledge the shadows as well as the triumphs of their early presence in this country. By doing so, they may discover a more grounded and generous foundation upon which to build their identity. Dark’s novel offers a model for such engagement. It demonstrates that when the past is approached with empathy and critical attentiveness, it becomes a source of insight rather than burden.

In the end, the novel extends its reach beyond the Greek-Australian community. It speaks to anyone who has grappled with the inheritance of migration, who has searched for belonging across cultures, or who has inherited a story that felt fractured or incomplete. Through Ghikas, Mary and their companions, Dark affirms that identity is shaped by the choices we make in adversity and by the compassion we extend to others. The story becomes a testament to resilience, to the capacity of individuals to craft meaning from dislocation and to the enduring human desire for home, even when home must be remade in unfamiliar soil.

The great achievement of Son of Hydra lies in its refusal to present origins as static. It shows that every legacy can be renewed through mindful retelling. As readers step away from its final pages, they may feel invited to carry forward a more generous understanding of the past, one that embraces complexity and honours all who contributed to the story. In doing so, the novel leaves us with a sense of uplift, encouraging us to walk our own long road with openness, integrity and hope.

The original article: belongs to NEOS KOSMOS .