Digital technologies – bane or boon for migrants seeking asylum in Europe?

Source: InfoMigrants: reliable and verified news for migrants – InfoMigrants

EU member states are increasingly relying on technology to remove backlogs in the asylum system, to reduce irregular border crossings and even to forecast displacement patterns. But a new report shows how automating migration and asylum processes can disadvantage migrants, asylum seekers and refugees, and even violate their human rights.

Technological tools are increasingly being tested and used on refugees and asylum seekers in the European Union: Lie detection, document verification, autonomous surveillance, monitoring migration flows, algorithmically matching migrants with communities — the list is long, and growing.

Amid this proliferation of technologies designed to help government agencies of EU countries automate decisions, NGOs and researchers have been issuing warnings against the potential downsides of deploying these technologies at scale in the context of migration.

On June 14, the European Parliament voted in favor of the AI Act, the world’s first comprehensive regulation of artificial intelligence. While the decision to adopt a ban on mass surveillance methods like facial recognition technology, human rights organizations say the bill in its current form lacks protections for people on the move, highlighting the potential risks that such digital technologies continue to pose for migrants, refugees and asylum seekers.

“The Parliament failed to ban discriminatory profiling and risk assessment systems, as well as forecasting systems used to curtail, prohibit and prevent border movements,” Amnesty International stated in a press release from June 14.

“There is no human rights compliant way to use remote biometric identification,” the statement added.

Derya Ozkul, Senior Research Fellow at the Refugee Studies Centre at the University of Oxford, says that AI-based technologies pose a “significant threat” to migrants and especially to asylum seekers.

“Automating decision-making processes can help some applicants to have a speedier response to their application, but the new risk assessments can disadvantage and even discriminate against others,” Ozkul told InfoMigrants.

In January, Ozkul published the results of a year-long study about this very topic. The 76-page report, titled ‘Automating Immigration and Asylum: The Uses of New Technologies in Migration and Asylum Governance in Europe,’ maps out the existing uses of new technologies across immigration and asylum systems of the EU and member states.

The report, published as part of the ‘Algorithmic Fairness for Asylum Seekers and Refugees’ (AFAR) project led by the University of Oxford’s Refugee Studies Centre and four other European institutions, differentiates three stages where technology is being used in the migration context:

before arrival in Europe, at the border, as well as within the EU territory.

Read more: French police deploy drones at Italian border to track migrants

Before arrival in Europe

There’s a number of tools the European Union and its member states have at their disposal before migrants even arrive on EU territory. According to the AFAR report, they fall into the categories of forecasting, risk analyses and automated processing of applications for visas.

The tools used at this stage show how technology has the potential for both positive and negative outcomes, according to Ozkul.

“In theory, forecasting tools can prepare humanitarian organizations and states for the arrival of large numbers of displaced people, but given the current political environment, this seems very unlikely. If these tools are employed by state authorities, they can potentially lead to even more pushbacks at the EU borders, so they are too risky,” Ozkul told InfoMigrants.

According to the report, one forecasting tool used to predict the number of people seeking to reach Europe using irregular means is the Early warning and Preparedness System (EPS). Developed by the predecessor of the European Union Agency for Asylum (EUAA), it uses various sources of big data including Google Trends, EU border agency Frontex databases and its own information about asylum applications and recognition rates to forecast trends.

According to the report, the “machine learning-based algorithm then seeks to anticipate which events will cause large-scale displacement” — such as natural disasters, wars and pandemics. This is in order to “estimate the ensuing number of asylum applications in the EU for up to four weeks ahead.”

On the other hand, these tools can also be used to increase border surveillance and to make it more difficult for displaced people to reach EU territories, the report adds.

“In other words, these tools risk supporting practices to deflect and deter migration rather than facilitate it,” Ozkul explains.

One tool still at the project stage is the EU-funded EUMigraTool (EMT) tool, one of whose aims is to “provide predictions of public sentiment towards migration” as well as “the identification of risks of tensions between migrants and EU citizens.”

Some EU member states and organizations are also developing their own tools to forecast displacement and migration trends, such as the ‘Predict‘ and ‘Foresight‘ projects, which are developed by Germany’s Foreign Office and the Danish Refugee Council (DRC), respectively.

Read more: UK signs contract with US startup to identify migrants in small-boat crossings

New technologies at the border

Some of the most controversial tests and uses of automated decision-making tools, according to author Ozkul, are currently being employed at the EU’s external borders. The aim of these tools, which fall in the categories of document verification, risk analyses as well as behavior and emotion recognition, is to check whether “documents and narratives” provided by potentials immigrants are valid and authentic.

One of the EU countries that have further developed such document verification technologies are the Netherlands, where the Immigration and Naturalisation Service (IND) are already using AI-based software to scan residence permits, birth certificates and other documents to detect identity fraud.

“‘Fraud detection’ technologies have been developed, based on, or promote the assumption that some of the travelers are lying, or may be lying, to gain access to the territory or obtain residency rights in the country,” Ozkul told InfoMigrants.

Among the most “dangerous” ways that identity verification technologies are being tested and used, according to Ozkul, is lie detection and behavior analysis at the border. While the latter was developed via the EU-funded TRESSPASS project, the former was tested as part of the EU-funded ‘|BorderCtrl‘ project in Hungary, Latvia and Greece.

IBorderCtrl has been severely criticized by civil society organizations, members of the European Parliament and academics like Ozkul.

“The main point of criticism has been around the technology’s ability to accurately assess human behavior,” she says. “It has been suggested that these types of assessments can lead to biases against people of different color, gender, age, and culture.”

According to the findings of one academic article about IBorderCtrl, European men had higher rates of accuracy compared with women and non-European men and women.

“But beyond concerns around accuracy, we need to question the very idea that migrants need to be interrogated through such technologies before being accepted to a territory,” she explained.

Read more: Digital borders — EU increases use of technology to monitor migration

New technologies after arrival

Another potentially dangerous use of verifying identities and narratives of migrants, Ozkul says, is the practice of extracting mobile phone data at border areas and as part of the asylum procedure.

According to a 2017 report cited in the AFAR study, confiscation of mobile phones and other devices was considered standard practice in countries including the Netherlands and Estonia, while it was seen as optional in Croatia, Germany, Lithuania and Norway.

Currently, mobile phone data analysis is actively carried out in the Netherlands, Germany, Norway, and to some extent also in Denmark.

In Germany, for instance, asylum seekers without sufficient identity documents must hand over and unlock their mobile device as part of the proceedings. The phone’s data is then routinely extracted, leading to a result report, which contains information on geodata and country codes related to incoming and outgoing calls, among other things.

While German authorities say a result report is only one of the files decision-makers take into account while processing cases, the exact impact of such reports on the actual decision-making is unknown, Ozkul stresses.

“Civil society organizations, like the Society for Civil Rights, criticized this practice extensively due to its violations of privacy, lack of meaningful consent, lack of necessity and proportionality, and finally lack of transparency as to the opaque nature of the software,” she told InfoMigrants.

Further potentially dangerous technologies used in immigration procedures, Ozkul says, include automated risk assessments and profiling methods to screen the identity of travelers.

In the processing of applications for the UK’s EU Settlement Scheme, introduced after Brexit, for example, those without national insurance numbers are reported to lack sufficient evidence of residence in the country.

“In particular, vulnerable groups are reported to have problems accessing digital systems or having their details verified in automated checks,” Ozkul said.

‘Unknown impact on fundamental rights’

Another highly problematic way to use automated risk assessments, according to Ozkul, will be through interoperable information systems like the European Interoperability Framework (EIF).

“This new framework will completely transform the traditional way to calculate the risk of overstay,” Ozkul said. Even the EU itself does not exactly know what these new systems will bring about, the latest Fundamental Rights Report of the EU Rights Agency says.

One of the systems introduced under the EIF is the recently expanded Schengen Information System (SIS). Originally established in 1995, the electronic search system is now in operation in 30 European countries. As the largest information exchange system “for security and border management in Europe,” it allows EU member states to store and share biometric data such as fingerprints, handprints and DNA records of wanted persons, with the goal of curbing irregular migration and managing crime.

“The EU IT systems are just coming into operation, and we are still discovering how several aspects work together. Their potentially vast impact on fundamental rights therefore remains partly unknown,” Ozkul stressed, adding that there is a need to critically explore how these systems will transform state borders in the long run.

Read more: In post-pandemic Europe, irregular migrants will face digital deterrents

Technology: a double-edged sword

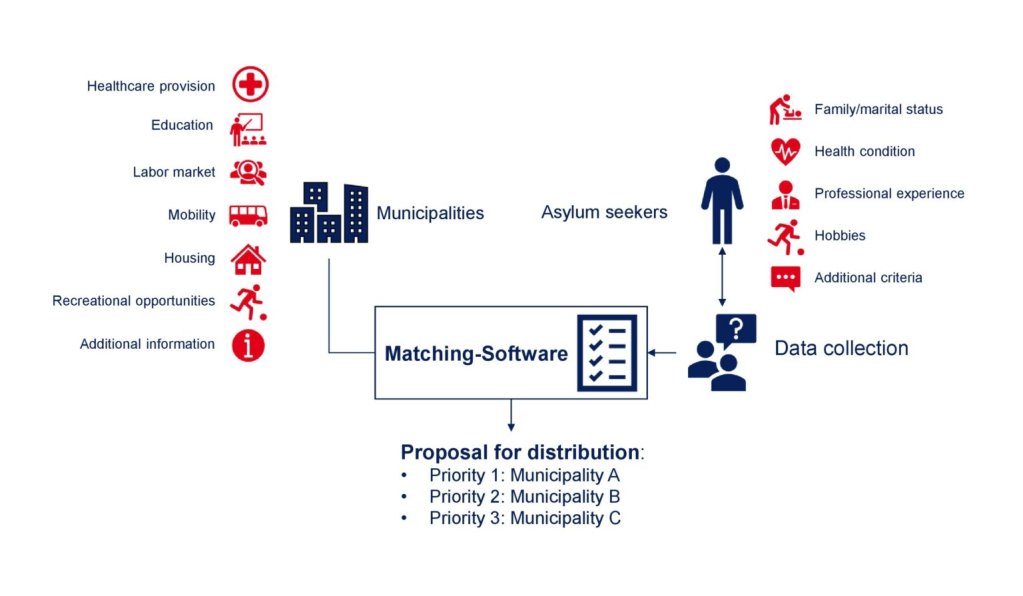

Among the positive uses, according to Ozkul, are matching tools developed to find adequate settlement places for recognized refugees.

Germany’s Match’In project, for example, seeks to place asylum seekers and refugees in communities with the help of a matching algorithm. Fed with relevant criteria of the host municipalities, such as its employment opportunities, and of the migrants, such as their professional experience, the algorithm matches offers and needs, and makes placement recommendations.

A similar piloted project — GeoMatch — has led to significantly better labor market integration among refugees resettled with a matching tool in the US, Switzerland and the Netherlands.

Despite these encouraging applications, Ozkul thinks the risks and potential for negative outcomes for asylum seekers and refugees outweigh the benefits of automated decision-making technology.

“Migrants’ interests and voices have generally not been included in the design and the decision to employ many of them,” Ozkul told InfoMigrants.

Moreover, she highlighted that she believes that automating decision-making processes could lead to discriminatory outcomes — for example when technical vulnerabilities, mistakes or biases in other data systems translate to mistakes in the processing of applications.

“Yet again beyond concerns around accuracy, we need to question how these technologies transform mobility, and what their social impacts are,” she said.

The original article: belongs to InfoMigrants: reliable and verified news for migrants – InfoMigrants .