From battlefields to new beginnings: The Anzac journey of the Segal Family

Source: NEOS KOSMOS

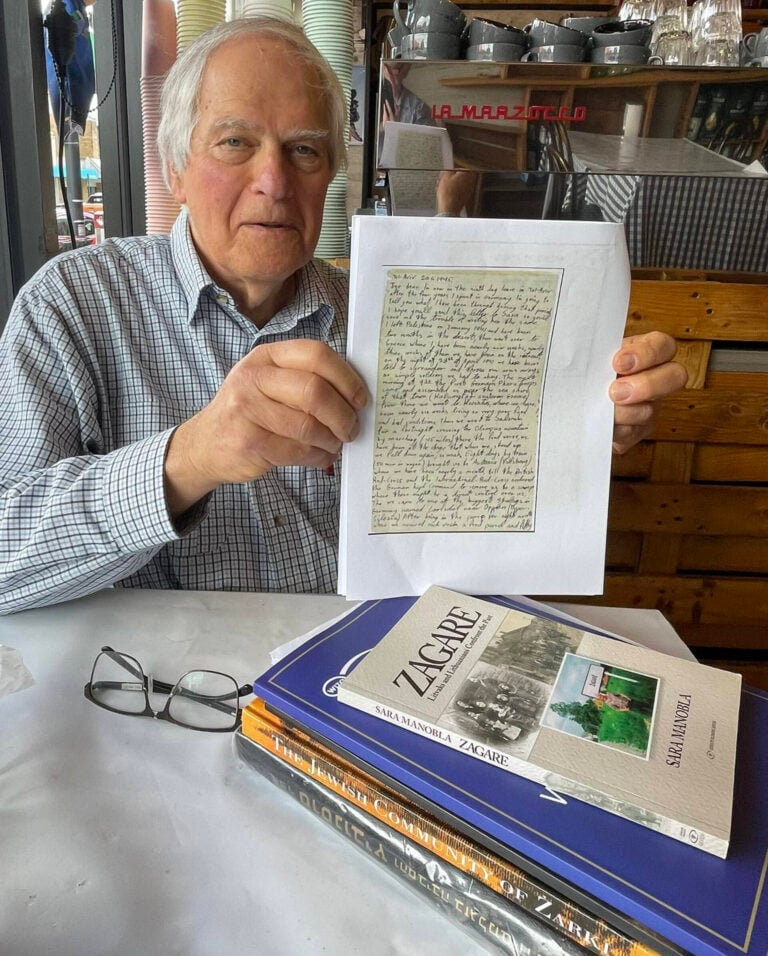

Many readers will know Aron Segal from his attendance at Hellenic commemorative events held in Melbourne. But not many will know of his family’s rich connection to Australia’s Anzac tradition, including the Greek Campaign of 1941. Recently, I sat down with Aron and listened as he recounted his family story. It is a tale of migration, familiar to many readers.

Russia to Kalamata: The start of the Segals’ Anzac story

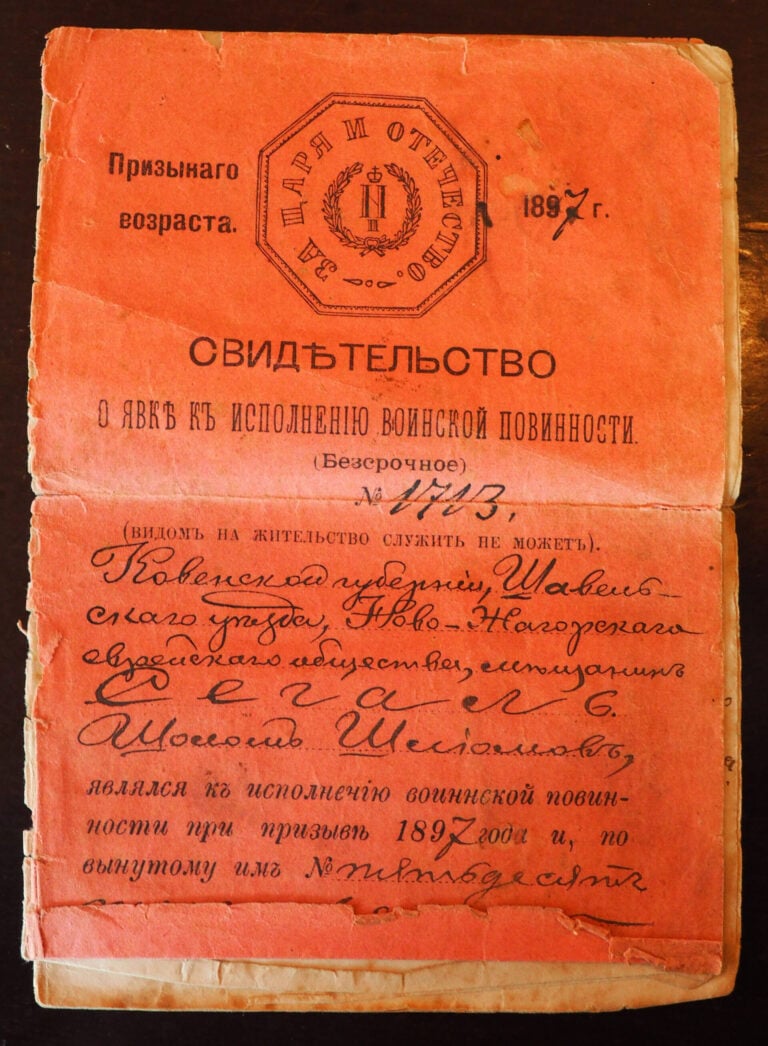

Aron’s family military history stretches back to Imperial Russia, with his relative Solis Segal, who was conscripted into the Russian Imperial Army in 1897. He would leave Russia and arrive eventually in Portland in 1910, where he would establish a draper’s shop. But we should begin the story by travelling forward in time to Kalamata in the dark days towards the end of the Allied campaign to save Greece from Axis occupation.

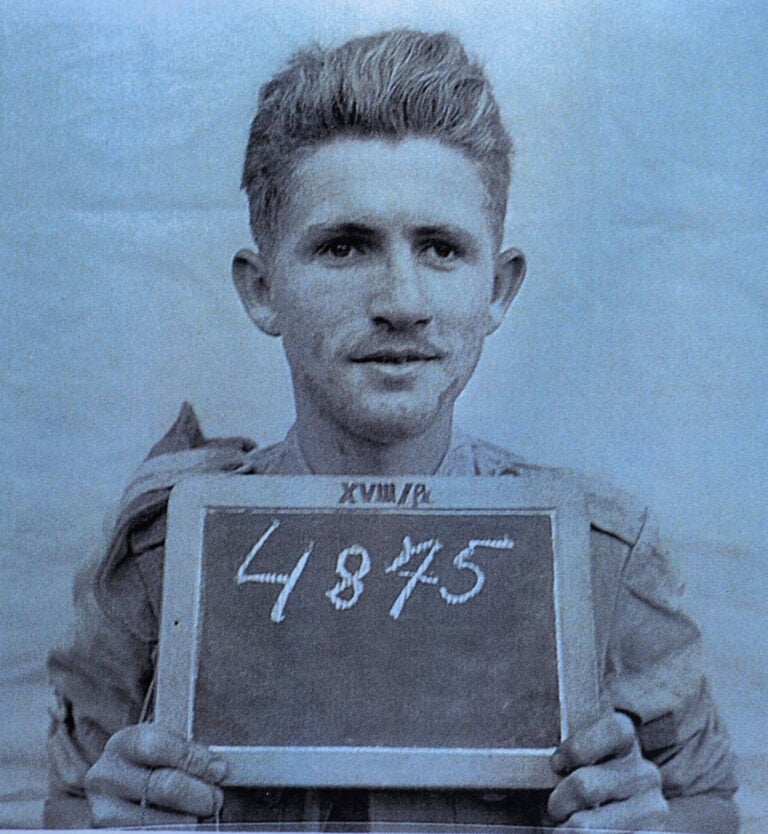

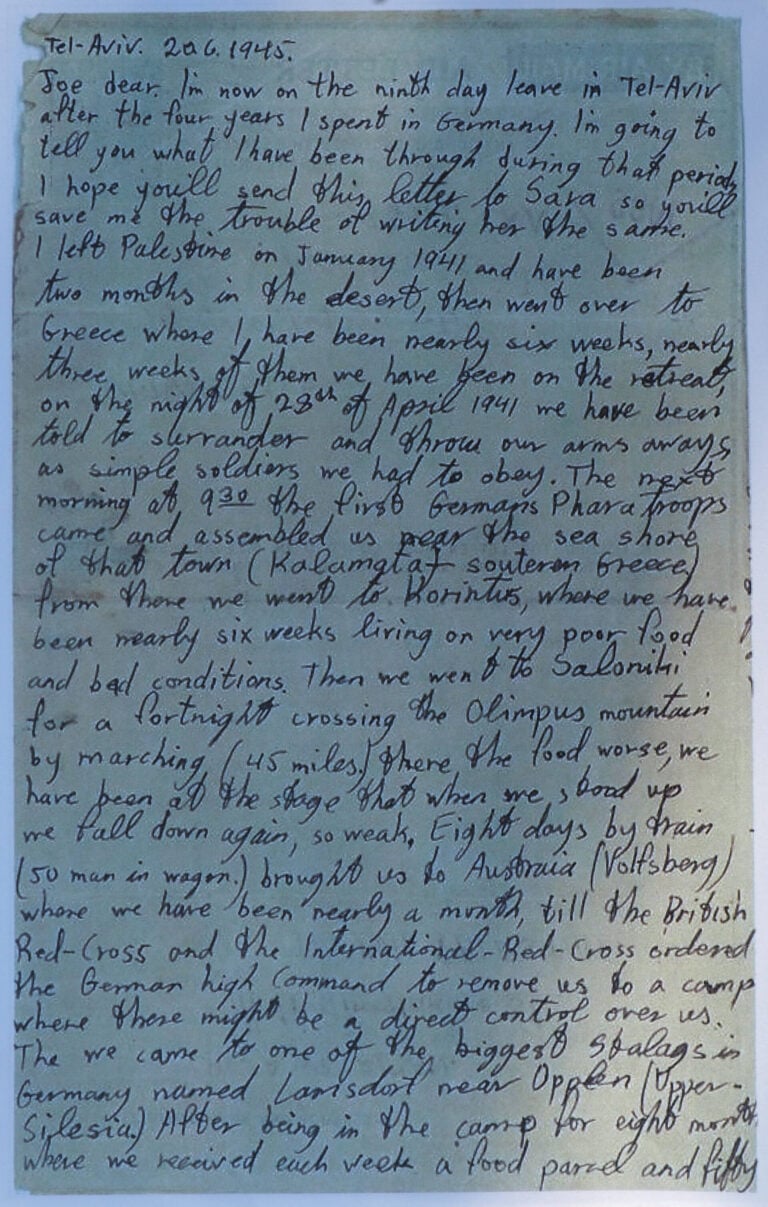

The Allied forces – comprising principally British and ANZAC troops– joined with the Greek Armed forces facing the enemy onslaught. The Allied forces included several ancillary units such as those from Cyprus and Palestine. The latter included the Palestine Labour Corps, raised in the British Mandate era Palestine and comprised largely of Jewish members. One of those men was Aron’s uncle, Aron Wajcma,n who was born in the Polish town of Bedzin in 1922, and had moved with his family to Palestine in the mid-1920s. It was here that he joined the call to fight fascism by joining the Corps. After the war, he would record his experiences of the Greek campaign in a letter to relatives, now in the proud possession of his nephew in Melbourne.

The campaign had seen Corporal Wajcman’s unit serve over the length of Greece, supporting the Allied frontline forces and being subjected to enemy air attacks as the Allied forces retreated. He writes of his six-week Greek campaign comprising three weeks of retreat. The Allied forces would retreat to a number of ports across southern Greece, where they would await evacuation. One of the most significant evacuation ports was Kalamata, with its waterfront facilities and large bay. By 28 April, some 18-20,000 Allied troops had made their way to the harbour, by truck and by foot. While over 9,000 would be successfully evacuated, some 8,000 would not. One of those was young Aron.

While some non-frontline troops were evacuated – some from Trahila in Mani, photographed by Australian Private Syd Grant aboard an evacuation ship – most did not. In the harsh realities of war, the limited evacuation space aboard the evacuation ships was reserved for fighting troops, not engineers or drivers. Australian accounts reveal that many of these troops had to be forcibly removed from evacuation ships or stopped at the harbour front by armed troops policing the evacuation. A sad end to a bitter and tragic campaign.

Prisoners of war: Survival, sacrifice and the struggle for liberation

Aron would have watched the last evacuation ship leave the harbour on the evening of 28 April. As he writes on that night, they “were told to surrender and throw our arms away, as simple soldiers we had to obey.” He goes on to describe the arrival of the German forces in Kalamata at 9.30 am the next morning. Aron and thousands of other troops – including many Australians such as the 2/6th Battalion’s Captain Albert Gray from Red Cliffs, who had taken part in the battle of Kalamata waterfront the night before – were now prisoners. Aron writes that it was German paratroops who ordered the men to assemble at the Kalamata waterfront.

Red Cross documents revealed that Aron was taken prisoner on 29 April and was soon taken to the POW transit camp established by the Germans at Corinth. A vermin-infested disused former Greek Army barracks; the thousands of Allied prisoners held here would remember these days and weeks with disgust. Aron writes of being there for six weeks, “living on very poor food and bad conditions.” The camp would soon be closed and the prisoners sent to the larger transit camp at Thessaloniki, having had to march 45 miles across Mount Olympus. Here he stayed for 2 weeks, where “the food [was] worse”.

He describes the depleted condition of the prisoners at Thessaloniki – “we have been at the stage that when we stood up we fell again, so weak”. Soon they were on their way again, leaving Thessaloniki by train, with 50 men to each wagon, as they made their way to their final prison camps in Germany. I have written previously in Neos Kosmos about the Corinth and Thessaloniki POW camps. Aron would be held in the Stalag 18 camp at Wolfsberg for a month before being transferred to Stalag 8B in Lamsdorf, along with other Allied veterans of the Greek campaign.

Aron was one of a group of 12 prisoners who were relocated to work on a farm outside Ratibur in 1942, where they would be based for 34 months. He would write that while on work details to surrounding towns and villages, he would witness victims of the Holocaust in the surrounding region, suffering “terrible conditions”, Aron and his fellow prisoners sharing what food and clothing they could with them. It is sobering to think that this Allied soldier, a veteran of the defence of Greece in 1941, witnessed these terrible events first-hand. His service in the British Army saved him from the destruction of many of his fellow Polish Jews by the Nazis.

As the war drew to a close, Aron and the prisoners took part in the infamous forced marches further into Germany as the Germans fled the advancing Soviet forces. It was while at a camp in Frankfurt-Am-Main that Aron and his fellow prisoners were finally liberated by US forces in April 1945, Aron was repatriated to England and, after a period of recuperation, returned to Palestine. A number of his fellow unit soldiers did not return; their graves remain on Greek soil at Phaleron War Cemetery. These include 40-year-old Private Gelbart and Sergeant Shoner, both killed as the Greek campaign on the mainland drew to an end.

A Legacy of service: The Segal family in two World Wars

Aron Wajcman’s service alongside the Anzacs in Greece is only a part of the wider Segal family’s Anzac service. These include five relatives who served in the Australian Army in the Second World War and one who served in the Australian Army in the First World War. The latter was Private Adolph Cantor, Aron’s second cousin once removed. Born in Zagare in Imperial Russia (now part of Lithuania) in 1876, he had initially immigrated to the US in 1889 before finally arriving in Australia in 1902. After a short period in Tasmania, Adolph moved to Warrnambool, where he continued his work as a draper.

Before enlisting in the 14th Battalion in 1916, aged 39, Adolph had married, joined the local rifle club and become a naturalised Australian. He served with the AIF’s Administrative Headquarters in London, where his service was recorded as “very good” before being discharged as medically unfit in 1917.

Those who served in the Second World War included two who were killed on active service and three who thankfully survived, one being Aron’s father Harry Segal. Born in Zagare like his relative Adolph Cantor, Harry had arrived in Australia in the late 1920’s having been sponsored by an uncle who operated a pearling business in Broome. At 33 years old, Harry enlisted in 1943 into the 121 Australian General Support Company in Alice Springs and served out the war in Australia, being discharged in May 1945. 26-year-old St Kilda storeman and packer Joel Wiseman – Aron’s uncle, who was also born in Bedzin– enlisted in 1942, serving in New Guinea with various maintenance units.

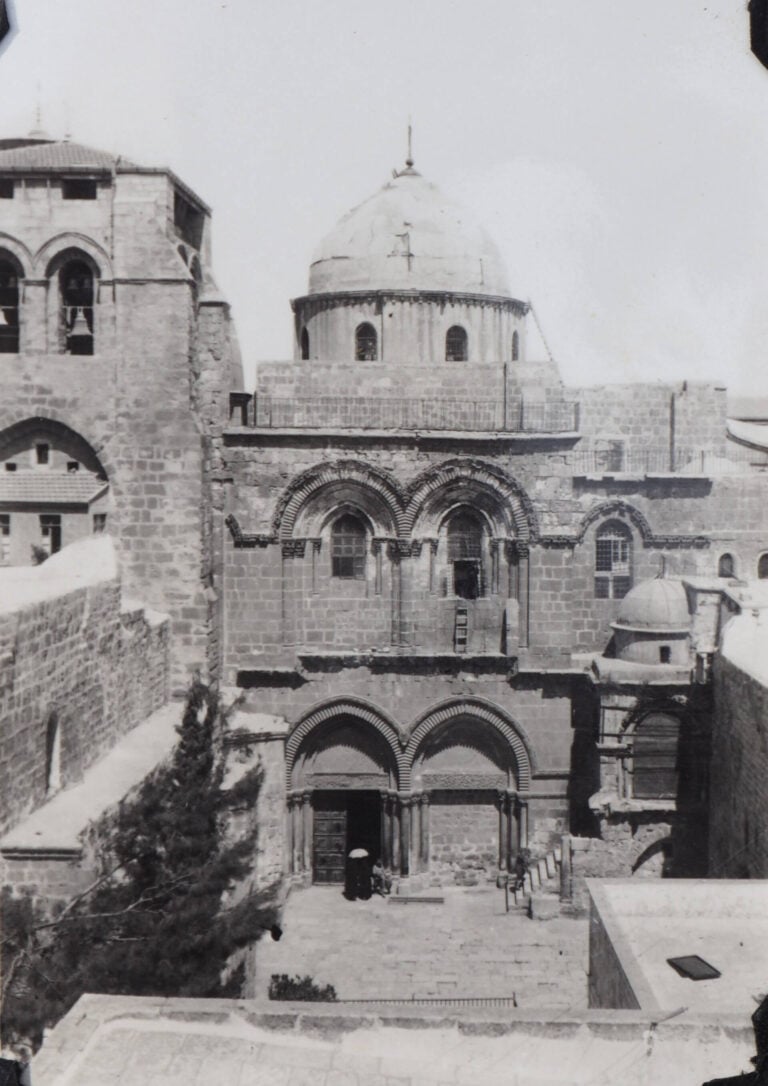

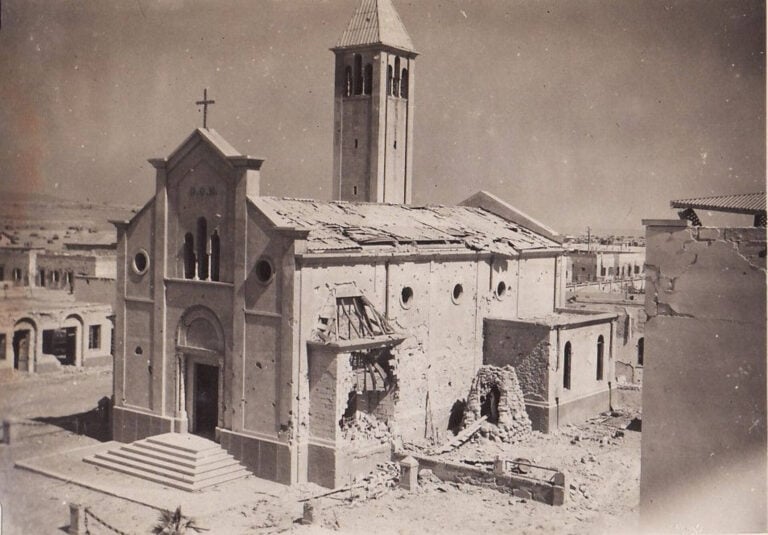

Staff Sergeant Boris Segal – the son of the former Imperial Russian Army soldier Solis – joined up at Portland in 1940 aged 21. He would serve in both the Middle East and New Guinea campaigns, serving with both the 2/2 Australian General Hospital and AIF 9th Division Headquarters. He would bring home an amazing collection of photographs documenting life in British Mandate-era Palestine.

Aron’s two Anzac relatives who would be killed in the war would die in distant battlefields serving the new country that they had made home. Lance Sergeant Abraham Beth-Halevy had been born in Kalish in Imperial Russia (now Poland) in 1913 and was Aron’s mother’s fiancé. Enlisting in 1942, he was serving with the 2/12th Battalion when he was killed in action during the vital battle of Shaggy Ridge in New Guinea in January 1944. He is buried in Lae War Cemetery. Major Zelman Schwartz was a senior medical officer who commanded the 2/4th Australian General Hospital in the Middle East. He had also been born in Imperial Russia, arriving in Australia in 1902. The 42-year-old Zelman was living in Malvern when he joined the Australian Army Medical Corps in 1940. He was killed along with many staff and patients in a daylight German bombing raid on the clearly marked hospital on 10 April 1941. He is buried at the Tobruk Cemetery. I remember Tobruk veteran Gil Easton telling me of his being in the hospital when it was bombed.

The Jewish volunteers who served during the Gallipoli campaign, about whom I wrote before, also came to Lemnos. Just as their comrades in the Second World War in Greece did, they performed vital engineering and supply functions in support of the campaign. They serve as a reminder that the Allied campaigns in Greece during both world wars involved service personnel from around the globe.

These connections would stretch back to Australia and on to other Anzac campaigns. The service of the Segal clan should be remembered.

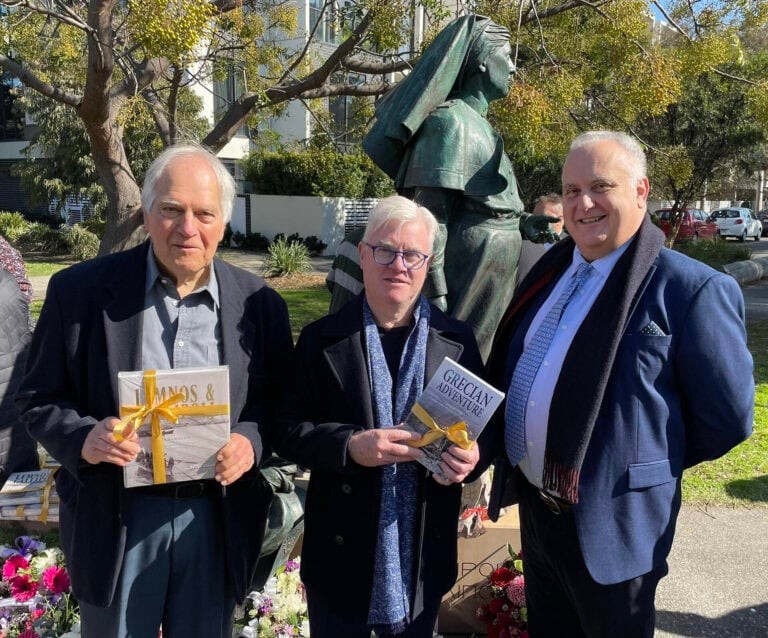

*Jim Claven OAM is a trained historian, freelance writer and published author; his books include Lemnos & Gallipoli Revealed, From Imbros Over The Sea and Grecian Adventure—he is the Associate Producer of the documentary on the 1941 Greek campaign, Anzac The Greek Chapter.

The original article: belongs to NEOS KOSMOS .