Giving migrants a voice via Italian lessons in Trieste

Source: InfoMigrants: reliable and verified news for migrants – InfoMigrants

In the Italian city of Trieste, free Italian lessons are offered by volunteers to migrants, asylum seekers and refugees from 55 countries. They run twice a week from October to May every year and are helping to foster a brighter future for those who decide to stay in Trieste. They also offer a voice to those who otherwise might have remained invisible, say organizers.

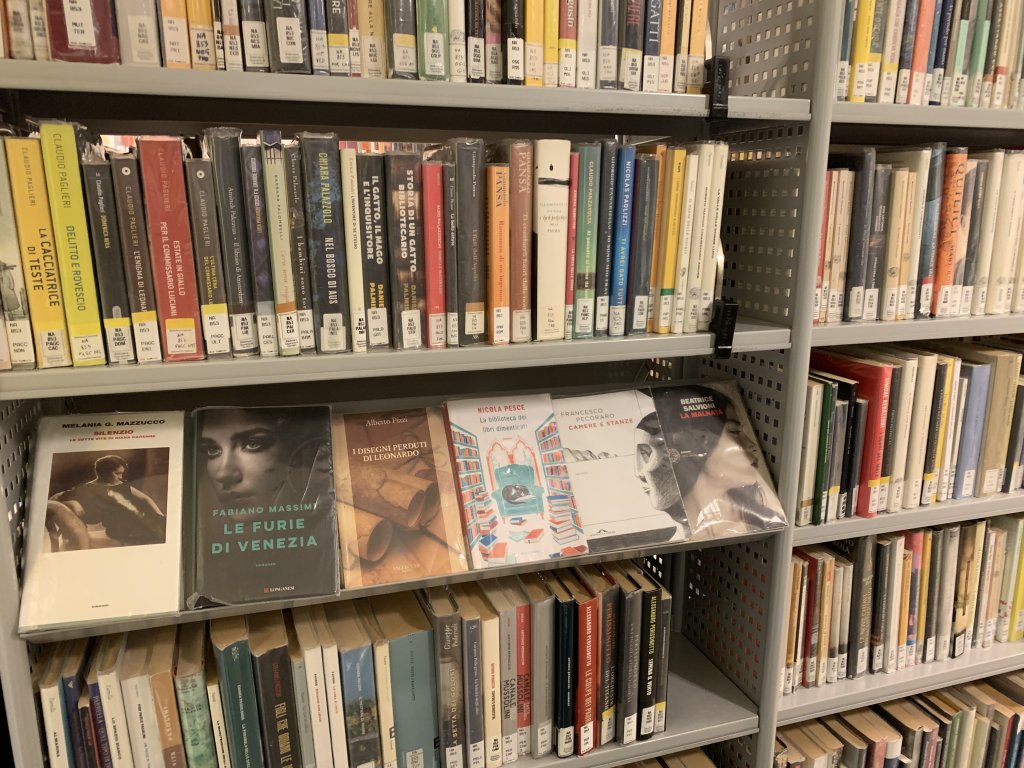

Outside, the dark streets glisten with rain, but inside Trieste’s communal library a warm glow invites migrants, asylum seekers and refugees in, to take part in a session of twice-weekly small group language learning.

“We are trying to create a dialog and a bridge between the people who arrive in Trieste and the people who live here,” explains Serena Pulcini, one of the organizers of the courses and part of the cultural association ARCI in Trieste – a nationwide association that offers services and courses that support the social and educational needs of various communities in Italy, including migrants.

Trieste, in the very north-eastern corner of Italy, is virtually on the Slovenian border, and so tends to be the first Italian town people arrive in after traveling the Balkan route. Many of the migrants who arrive don’t stay long, say those who work for migrant organizations in Trieste, as around 80 percent are aiming for other countries in Western Europe, France, the UK, Germany or Scandinavian countries, but for those who do decide to stay, Italian lessons run as a collaboration between ARCI and Trieste’s municipality can be invaluable.

Highly motivated

“The people who take our lessons vary quite considerably. Some might only be here for a short time, others have already been here for several years. Some we might see for one year and then we won’t see them again. However, the people who attend our lessons between October and May are generally highly motivated to learn. Especially because this library is not that central, many people may have been working all day long and so to then come and learn Italian on top of that, they are really demonstrating that they want to do this,” says Serena, calmly and expertly dealing with a variety of questions and queries from participants and their children, as she passes through the library explaining how it all works.

The courses on offer, explains Serena, range from offering reading and writing skills for those who might have been illiterate but have learned to speak Italian, to improving the communication and language skills of migrants who may have already been in Italy for several years.

“We began our work for those who were really needing to learn Italian, or even learn to read and write, as we believe that being able to speak good Italian is a good thing for everyone in society. Speaking the language gives you a voice and allows you to be present and have a presence in society and cancels out the invisibility that can dog you if you do not have a voice. Once you can communicate, you are a person who can begin your life in a new country,” says Serena.

Students came from 55 different countries last year

Last year’s courses offered Italian to people from 55 different countries. People from Senegal formed the largest single national group, with people from Kosovo, Pakistan, Morocco, Afghanistan and Tunisia following behind.

Quite a few of the participants have brought their children to the library, too. Some play games with the organizers, while others sit in their prams while their parents learn. “You see that there are lots of women here with tiny children, at 8 pm in the evening in a place which you can only reach with the bus, so it really shows how much desire there is to learn,” explains Serena with a smile.

The average age of course participants last year was around 32, the majority of all participants were between the ages of 20 and 40. They also had 48 people between the ages of ten and 20, 39 people between the ages of 40 and 50, ten between 50 and 60 and ten who were older than 60.

‘A playful approach’

“We teach grammar, but you don’t immediately know you are learning grammar here. We try and create a structure where people can communicate. To be able to go to the doctor, or to understand which medicines they might be prescribed at the pharmacy, or what to call different clothes so they can buy the right garments they might need their job or in life. We try and teach them how to get on in daily life,” says Serena.

“We try and approach our lessons in a playful and light way. Also, because you must remember this is the evening, people come after a long day at school or work, so they want to learn, but it has to be accessible.”

It seems like their approach is working. After the courses finish at 8 pm, a line of students congregates to explain how much they love studying here. People can join the courses with no questions asked about their status or their backgrounds, in order to offer as much accessibility as possible.

‘People here are warm, friendly and kind’

Natasha is from Bosnia and is already attending the course for a second year. Currently studying level three, Natasha’s Italian is already fairly confident: “We all have different mentalities here and come from different countries and the teachers are so good because they make sure you understand in your own way, and they keep going until you really understand. This course is so helpful. I am not working, because I have a small child at home, but I hope to be able to work in the future. My husband’s parents and my parents are in Bosnia and Macedonia and so we have no one to look after our child here, but once I have finished my course this year, our child will be able to go to nursery and then it should be possible for me to find work. I hope to work as a makeup artist in a company like Kiko (a Milanese makeup company) I have several friends who work as makeup artists. I love being in Italy and here in Trieste, people are really warm and friendly and kind. I like the sea here; I really like it.”

Ascemi from Afghanistan is also a big fan and also a student in level three. “I have been in Italy for three years and living in Trieste. It was a long journey getting to Italy. I work as a gardener with a cooperative. I actually did that work in Greece when I lived there for seven years, from 2003. But then I returned to Afghanistan and escaped again when the Taliban came to power. My family is in Iran, and they have completed all the forms now for family reunification. I really like learning Italian, but it is difficult.”

Fallo, a young man from Senegal, who flew here to join his father is still at a beginner level. Shyly, he explains how he loves learning Italian and how it will help with his training course, learning to install air conditioning units.

Mustafa, a 26-year-old migrant from Morocco has already progressed to level two. He explains that he wasn’t able to pursue much education in Morocco, as coming from a rural area, he was quickly put to work in the fields. But now in Italy, he is reveling in an opportunity to learn. Mustafa traveled along the Balkan route to reach Italy. Flying first to Turkey and then progressing over two months via Serbia, Hungary and Slovenia. He says the journey was hard and he was often scared. “I had to sleep outside, even when it rained, so I was sometimes soaking wet.”

Mustafa says he traveled with one friend, but they didn’t know anyone when they arrived in Trieste. At first, he says, he had nowhere to sleep, but “now I have found work and a place to stay. I am happy.”

Mohammed too is from Morocco. His journey towards Italy was a little easier as he arrived with a seasonal work contract. “I am 23 and I live in Trieste with my fiancé.” Mohammed works as a waiter and arrived in Italy a year and eight months ago. However, when his initial seasonal work permit ran out, he wasn’t able to convert it and continue working, so he began the process of applying for asylum. “That means I can’t return to Morocco, so I miss my friends and family a bit,” says Mohammed, “but I am happy here. I like the Italian mentality, people are really friendly and nice. I think they are the nicest people in Europe.”

Mohammed says that he doesn’t have grand plans or “big dreams. I just want a normal job, to get my papers here, see my friends and family and have a normal life.”

Homework helpers

Serena explains that the association runs a special training course for teachers who work for them and each year they also have apprentices, like Bianca, who is studying languages and translation at university and is shadowing a class with a view to volunteer teaching in the future. Bianca is also doing another course helping children with their homework, which is also a project offered by Arci.

That project offers help with homework to elementary and middle school children. It provides valuable support twice a week to both children and families, says Serena.

Reaching migrant mothers through their children is one of Serena and the association’s projects for the future. Some mothers can be difficult to reach, sometimes because they may not have studied in their own countries and sometimes because they are busy at home with the children.

Serena explains how she hopes that in future it might be possible to offer lessons to mothers as they come to drop off their kids at school. Learning the language, she thinks, is key to participating fully in society and to making improvements, for everyone.

Sometimes, explains Serena, it can also help the children of migrants, who often get placed in roles of great responsibility at too young an age, translating for their mothers or parents. This can upset the social balance in the family, thinks Serena and can have all sorts of knock-on effects for society and the individuals later on.

‘There is a lovely energy’

It is not just the lights of the library that glow warmly. The smiles on the students’ and teachers’ faces do too. Manuela has been volunteering with the project for nine years now. “There is such a beautiful energy here. People come from different backgrounds, but everyone is friendly and calm.”

57-year-old Erica, another volunteer teacher and a pharmacist by profession, concurs. “I began teaching a few years ago when my own children had grown up. I wanted to do something for the other ‘children’ in the world. They are not my children, but it is as if they are. When I first started, I mostly taught the absolute beginners. Now I teach a level two class, where people know quite a lot, but they still want to improve. There is a lovely energy at the end of the year between the group, many of us become friends. It is such a privilege to see the integration that goes on between the young people from so many different nationalities and religions, traditions and cultures. Everyone learns how to get along and become friends and at the same time they learn tolerance. We try and celebrate everyone’s special cultural and religious days, and at the end of the year, everyone will bring in a dish from their country for the others to try. Through celebrating each person’s cultures and religious days, we are also able to explain and understand our own, so that everyone can share in everyone else’s. We sing and dance and share the foods from our countries, it is beautiful.”

Lessons take place in the Quarantotti Gambini library in Trieste, Via delle Lodole number 6 on Tuesday and Thursday evenings. The courses are oversubscribed and there is a waiting list. For more information, contact Comune di Trieste or the Italian association ARCI Trieste-Trst

ARCI also organizes homework help groups for children, both migrant children and Italian children after school on Tuesdays and Fridays at their center situated at Via del bosco, 17b. It is staffed by volunteers from ARCI and the Italian national volunteer association Servizio Civile (Civil Service).

The original article: belongs to InfoMigrants: reliable and verified news for migrants – InfoMigrants .