Ring of Richter: Why seismologists can’t see the faults… beneath their feet

Source: ProtoThema English

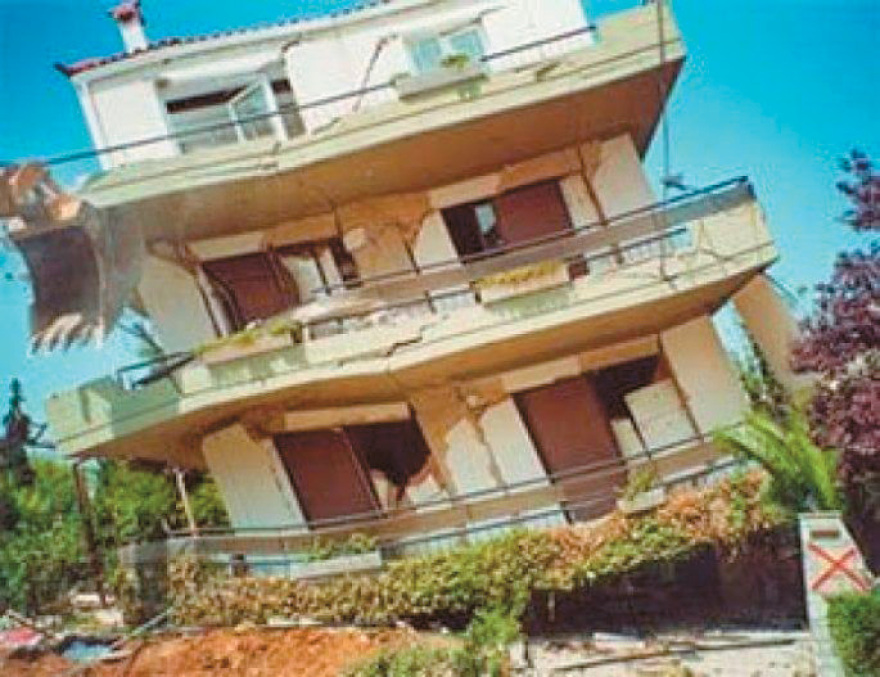

When the devastating earthquake hit Athens in September 1999, seismologists repeatedly made the most nightmarish observation regarding the fault that produced the deadly 5.9-magnitude tremor on the Richter Scale: “We know nothing about it.” By a cruel coincidence, last week’s earthquake (5.2 Richter) in Nea Styra, Euboea, which revived memories of ’99 for Athens residents, also originated from a fault unknown to the seismological community and therefore unmapped.

Scientists classify unmapped faults in Greece into two types: medium/large dynamic faults and small, local faults. Naturally, tectonic formations in the first category can produce the largest magnitudes and therefore the greatest destruction, while those in the second category usually cause only localized damage.

1981 Alkyonides 6.7R

After the triple earthquake of 1981 from the Alkyonides fault, an effort began to map the faults of Attica.

To illustrate the point, on the night of last Thursday, three small local faults caused minor tremors in Attica: the first, magnitude 2.5 Richter, occurred in Kifisia; the second, 2 Richter, in Chalandri; and the third, magnitude 1.2 Richter (non-reportable), in Kifisia. Typically, these faults are superficial and of low magnitude. Scientists explain that the main reason they haven’t been recorded or studied is that they are located in densely populated urban areas. “Imagine, for example, if we had to close Kifisias Avenue or evacuate apartment buildings to make cross-sections and measurements that would provide data on a local fault. I have a feeling people wouldn’t take it well,” explained a geologist to THEMA.

Submarine Faults

Another category is submarine faults, such as the one in Euboea that caused the 5.2 Richter earthquake, with a focal depth of just 13.6 km. The shallow focal depth explains the noise heard and why the tremor was particularly felt “mainly in Eastern Attica and nearly all areas of the Basin, because it was a shallow earthquake, very close to densely built areas, and obviously the taller buildings swayed more intensely,” clarified the president of the Earthquake Planning and Protection Organization (OASP) and geology professor at the University of Athens, Efthymios Lekkas. “Since this fault is underwater, we don’t yet have a complete picture of submarine faults.”

Lekkas adds that this fault cannot trigger nearby faults, like Oropos, or at least “there is an extremely small chance for that. In Oropos, we have several large faults capable of producing earthquakes up to 6–6.2 Richter. Our main concern initially was to determine the epicenter accurately, human mind and hand determining the epicenter. Once we did, along with data on the fault’s direction and movement, we concluded there are very few possibilities of activating another fault.”

Regarding the potential triggering of nearby faults, seismology professor Kostas Papazachos from Aristotle University of Thessaloniki compares it to “someone being sick and we don’t worry about them, but whether someone next to them will catch it. Right now, our focus is Styra.” He explains that the Nea Styra earthquake originated from a fault unknown to seismologists. At least historical evidence shows it does not produce large earthquakes.

Papazachos elaborates: “Strange as it may seem, we have no idea about the fault, we don’t know its dimensions. It’s a medium-to-low seismicity area. It has normal and strike-slip faults due to regional stretching. It has never produced large earthquakes that could destroy Athens. I believe it is typical for Euboea, around 5 Richter. Imagine, 5.2 Richter occurs every two months in Greece without follow-up. We’re not like Kefalonia, where a 7 or 6.5 Richter quake could happen tomorrow morning. There’s no potential for that.” He adds that even if a 5.8 Richter occurred, effects on the Basin would be minimal, limited by the offshore location and depth.

Mapping

The last time a small, local, unknown fault alarmed Athenians, pulling them from their beds onto the streets, was mid-December last year. A 1 km-long microfault with a focal depth of 8.7 km produced seven consecutive tremors from 2.3 to 2.7 Richter, centered in Agia Paraskevi. Mapping the epicenters from east to west revealed that the fault started near the Ministry of Infrastructure and Transport, extending east toward the end of Cholargos’ urban area, near Kifisias Avenue. Until then, it was unmapped.

Efthymios Lekkas explains that small tectonic structures (microfaults) can reach 6–6.5 Richter. This doesn’t mean they are necessarily dangerous, as many are offshore or deep. Mapping of Attica’s faults began after the 1999 Athens earthquake. Although several studies exist, including specialized ones for East and West Attica, the most complete mapping is a joint study by the University of Athens and the Polytechnic. However, some faults escape detection because they are identified via geophysical surveys, usually for large faults, which are nearly impossible in urban areas.

Major and Minor Faults

How many active small-to-medium faults have scientists recorded in Athens and what is their potential? “Several dozen,” says Lekkas. Most are too small to produce large earthquakes and damage, though exceptions exist, as the Parnitha earthquake showed, where proximity to urban complexes increases seismic risk.

Large faults previously unmapped have been found in Southern Euboea, Porto Rafti, Nea Makri, Saronic Gulf, Corinthian Gulf, Northern Parnitha, Kakia Skala, and urban areas. These have high potential and are closely studied. Many smaller and medium faults exist in northern and northwestern-western suburbs: Marousi – Melissia – Vrilissia – Gerakas, Chalandri – Agia Paraskevi, Ekali – Nea Erythraia – Drosia – Dionysos, and also Alimos – Elliniko – Argyroupoli – Glyfada, Salamina – Perama – Keratsini – Moschato, Stamata – Nea Makri, Zephyri – Kamatero, Aspropyrgos, Koropi, Fylis – Ano Liosia.

Intermediate-depth faults like those in the Saronic Gulf cause quakes up to 6.5 Richter, e.g., the 6.5 Richter August 1962 Akrokorinth earthquake.

Unknown-capacity faults remain a mystery. Scientists know them but lack data to conclude their strength or behavior, including how they respond to nearby tremors or their seismic acceleration, which often determines destruction levels. Examples include the Penteli, Rafina, and Spata faults.

Historic Earthquakes

1894 Atalanti 6.7R – The 34 km-long Atalanti fault produced two quakes, 6.7 and 6.4 Richter, killing 255 and destroying thousands of homes and infrastructure in Athens and Piraeus. It also created a 3-meter tsunami reaching 1 km inland and the “great gap of Locris,” over 35 km long.

Most Dangerous Faults

In Attica, the Alkyonides – Schinos – Kapareli faults are among the most dangerous, associated with deadly 1981 quakes. The Parnitha – Fyli fault, unknown until 1999, caused the catastrophic September 7, 1999, earthquake.

Oropos fault has produced significant quakes in the past (July 20, 1938). Large faults threatening Attica also exist in the broader region, including the Corinthian Gulf system and Atalanti.

Why Euboea?

Euboea lies in a geodynamically active zone between Atalanti and the Northern Aegean fault system, where the North Anatolian Fault terminates. This system, extending from Anatolia to the Marmara Sea and Northern Aegean to Euboea, includes segments capable of 9 Richter. Scientists have extensively mapped and studied it, most recently after the swarm in May, which included over 40 tremors, the largest 4.5 Richter in Prokopi Mantoudiou, Northern Euboea. In 2022 and 2023, intense seismic sequences occurred near Zarakes and Kymi, with tremors from 4.5 to 5.1 Richter.

Photos: Getty Images / Ideal Image, ARCHIVE

Ask me anything

Explore related questions

The original article: belongs to ProtoThema English .