Sophie de Marbois: The true story of the Duchess of Plakentia

Source: ProtoThema English

Eccentric, with striking appearances distinguished by her unique hairstyle and the translucent veils she wore over her head, almost always surrounded by massive shepherd dogs, and possessing a sharp wit that never went unnoticed, Sophie de Marbois was a novel-like figure — and not only by the standards of revolutionary Greece.

Born in an era when women had no right to education, the Franco-American noblewoman not only excelled in classical studies but also maintained close personal friendships with Napoleon Bonaparte, having been married to one of his aides-de-camp. Curious and adventurous, after traveling through the great cities of Europe, she reached the East and ultimately decided to settle in Greece.

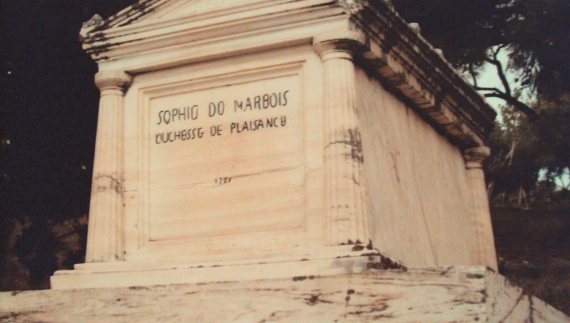

From early on, she sided with the Greeks in the War of Independence, befriended leading Greek figures — from Miaoulis to Mavrokordatos — was involved with the French Party, and displayed significant philanthropic work, especially supporting Greeks and Jews. Yet, she will forever be remembered as the woman behind the impressive mansion that today houses the Byzantine Museum in downtown Athens, and as synonymous with the wider Penteli area, where her tomb lies, with the nearby metro stop serving as a daily tribute to her memory.

Imperial Habits

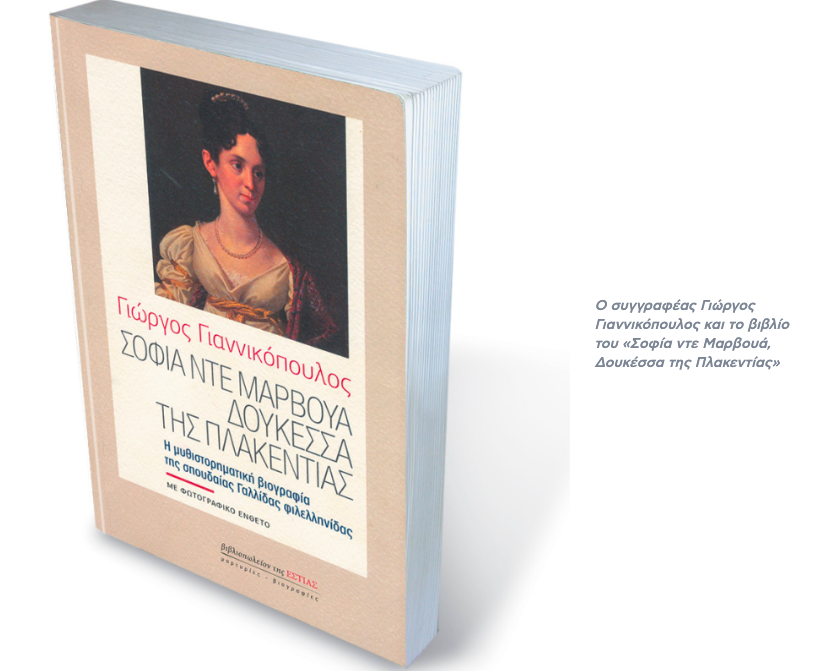

All these details are vividly brought to life for the first time in their full historical context in Giorgos Giannikopoulos’s book “Sophie de Marbois, Duchess of Plakentia” — accompanied by a photographic insert and recently published by Estia Editions.

The book’s original contribution is that the author attempts to tell the Duchess’s fascinating story in an accessible way, even for those unfamiliar with her history. For the first time, he conducted systematic research through multiple sources and an extensive bibliography (French, Greek, and American), as well as letters and newspapers from the period. Thanks to this thorough research, we learn previously unknown facts about de Marbois’s life, including her actual religious beliefs and the episode with the French doctor who tried to cure her daughter in Beirut, along with a full chronicle of Greece’s early years as a country. Importantly, the author compares his sources with references from other readings and books, offering us a comprehensive picture of Greece shortly after the revolution began.

We also discover many details about the direct connections between key figures in the independence struggle and foreign personalities, as well as the unified line linking the main actors of the world wars with Greek affairs: it’s no coincidence that the Greek aristocracy had close ties with influential foreign families, creating a network of influence and relationships.

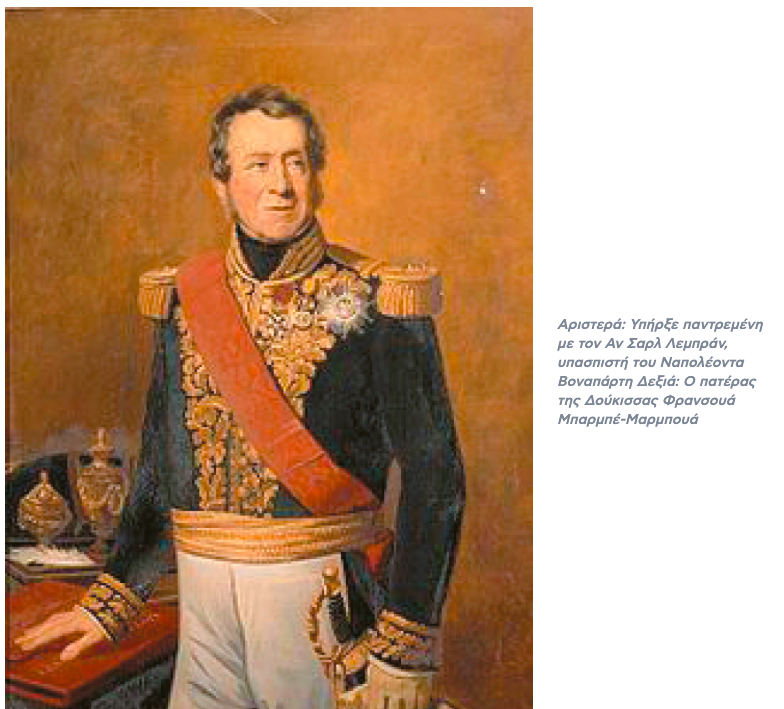

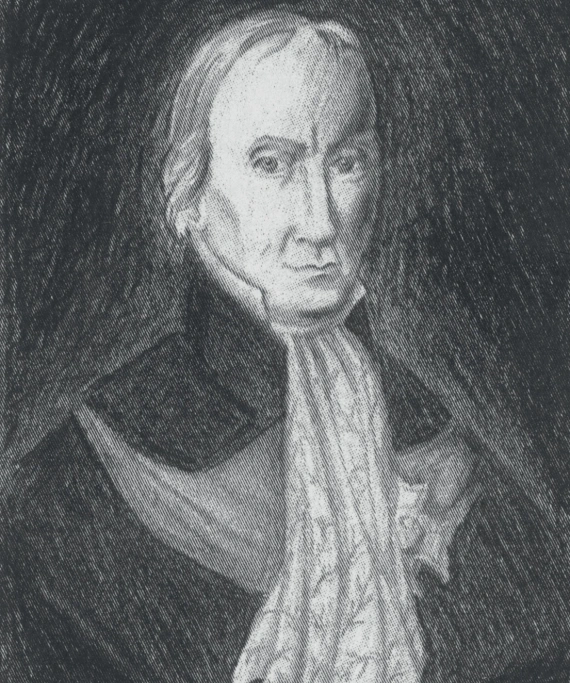

Even the Duchess owed her education and character to the diplomatic connections of her father, François Barbey-Marbois. She seems to have inherited his resilience and dynamism, as the author describes in a detailed chapter in the book. Barbey-Marbois nearly died when he was exiled under harsh conditions to Guyana, but after being acquitted, he returned to see his daughter Sophie accepted into the prestigious girls’ school of Madame Campan, who was not only head of Queen Marie Antoinette’s servants but also responsible for the queen’s dressing ceremony.

Having survived the revolution, Madame Campan taught young Sophie how to comport herself at court and ensured the ambitious girl acquired rare skills for her time.

Winning Napoleon’s Aide-de-Camp

This is how Sophie managed to win over Anne Charles Lebrun, a young officer of Bonaparte, whom she married in the grand Saint-Eustache Church in a Catholic ceremony, which explains why, even after separation, she never obtained an official divorce. At the same time, her mother began showing serious mental health issues, which caused considerable difficulties for Sophie.

Personal Struggles and Energy

To balance her personal dead-ends and abundant energy, Sophie took to horseback riding — and this image of a self-sufficient, energetic woman remained with her until the end of her life. After Napoleon’s powerful return in 1810, the young Sophie enjoyed privileged treatment, even if she no longer lived in the royal quarters as she did under Josephine Antoinette. Still, she had the unique privilege to be tailored by the same dressmaker as the Empress — Louis Hippolyte Leroy.

However, she suffered great loneliness as she awaited her husband’s return, once again from the front lines. At that time, Charles was with Napoleon’s Grand Army in the campaign against Russia, always serving as the Emperor’s aide-de-camp. Although her husband’s and her father’s relations with Napoleon went through ups and downs, Sophie remained loyal to him until the end — a loyalty duly appreciated.

The Philhellene

On the other hand, her relationship with her husband, Charles, and their return to Paris after the war — specifically to Place de la Madeleine — was far from happy.

However, the philhellenic passion gave her great motivation and defined her life’s course, replacing the sorrow caused by her mother’s illness and her troubled marriage. “The Duchess became interested in the Greek cause in May or June 1826, when she met Ioannis Kapodistrias at a social event in Paris. His strict manners won her admiration, alongside his unique and deep devotion to the Greek struggle,” notes historian Giorgos Giannikopoulos.

Kapodistrias’s sincere and selfless efforts to inform French officials and friends — such as the Duke of Orléans — about the Greek issue, emphasizing the need for powers to separate Greeks and Turks, were beyond suspicion. He asked for no reward for his actions, and the Duchess was willing to support these ideals.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions

The original article: belongs to ProtoThema English .