What Europeans – And Their Politicians – Misunderstand About Enlargement

Source: Visegrad Insight

Despite much discussion on the topic, there has been little actual preparation for EU enlargement. But this is not because of oft-quoted prejudices against the accession process, few of which actually hold water. Rather, much of the talk in EU capitals seems to be about inventing reasons not to enlarge.

There has been much talk about preparing Europe for the next enlargement. Recently, the European Commission announced major pre-enlargement reforms and policy reviews to begin in early 2025.

Despite abundant discussions about moving forward, the EU seems to be going in circles. “We must be prepared,” goes the usual mantra recently evoked by Commissioner Maroš Šefčovič.

Is this a result of prejudice against neighbours from outside the club? Or is it merely a lack of strategic foresight? Perhaps, when talking about the enlargement process, the EU must start thinking about the prospect of darker futures…?

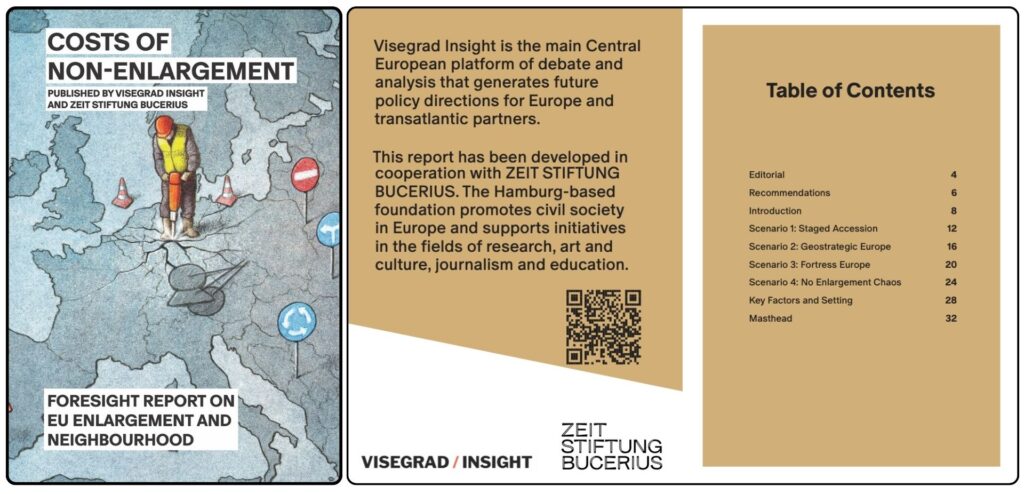

Earlier this spring, Costs of Non-enlargement foresight discussions brought together policy experts in Brussels and Berlin to set a new perspective on the future of the European neighbourhood and the EU accession process.

The discussions were built upon four scenarios, delineating how future EU enlargement could be achieved and what the consequences might be should Europe fail in the process.

By now, it is clear that two pivotal policy directions will steer the course of the union over the coming years: war and peace on the continent and the admission of new member states. The time to mobilise and shape this process is now.

Until recently, the most common prejudice against enlargement was that it is “too costly”. But it was not. Since the last big bang in 2004, the EU economy has increased overall by 50%, in what has been the biggest growth after the economic stagnation of the 1990s. The economies of France and the Netherlands grew by 30% and Austria by nearly 60%.

Ahead of the next series of meetings in Europe, we call to the public’s attention and confront some of the other unfounded prejudices often held against future enlargement.

Suggested reading:

Click here to read and download the report

Enlargement must ensure no democratic backsliding in the future (preferably forever)

There is a common sentiment that enlargement must be a golden bullet guaranteeing the future democratic performance of candidate countries. During our conversations in Brussels and Berlin, however, we agreed that it is inevitable that newly admitted countries will eventually face democratic backsliding, if not in the coming decade, then surely in the next one.

Poland and Hungary are the usual cautionary tales, and rightly so. Yet fewer people mention Geert Wilders’s recent electoral victory, developments in Italy, the fact that Belgium had no government for 652 days, or even more historical examples like the Haider affair of 2000 when 14 member states broke off bilateral relations with the far-right Austrian government.

Are we witnessing another facet of Orientalism towards the region? Surely. But there is another aspect of this problem. This prejudice tends to ignore the fact that democratic performance also depends on contingent political developments. It’s naïve to believe that entry requirements will suffice to prepare for whatever will happen in the next 20 years.

It would be even more naïve to blame that potential democratic backsliding on enlargement. To put it another way, no one blamed enlargement for the Greek economic crisis…

In fact, a set of entry requirements known as the “Copenhagen Criteria” are already so demanding that many of the richer and more “progressive” old EU member states might not have even qualified had it existed in their time of accession.

First of all, if this is true, how can we expect Bosnia and Herzegovina to qualify? Second, no matter how demanding the entry requirements may be, they would still be at the mercy of catastrophic events.

Take the migration crisis or the global financial crisis, where the collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008 unleashed a powerful impetus for democratic backsliding that is still not fully comprehended.

Entry requirements are not enough, and post-accession conditionality should be seen as the way forward.

“Enlargement is all about merit” – no, it’s all about politics.

The clearest testimony to that is the Bosnian candidacy status, which was granted not on the basis of merit but because of the parity with Moldovan candidacy. To be sure, sound institutional preparation should remain one of the main pillars of accession, but it should not be the only one.

The point here is to realise the broader reverberations of enlargement. We often tend to emphasise the volatile situation in the Western Balkans, including marked security threats and pronounced Russian presence in the region.

But can we imagine how much more unstable and dangerous the situation would have been if Romania and Bulgaria had remained outside the EU just because they didn’t meet the entry requirements? Susceptible to Russian interference, they would have added another burden to the stability of the entire region and made the situation even worse.

One may argue that both countries had already joined NATO in 2004, but given the current realm of hybrid warfare and how sophisticated foreign interference has become, EU membership comes as the most effective way of neutralising such security threats.

To reiterate, all of this would not have been possible if accession had been all about merit. Both countries were not institutionally ready to join the Union. Instead of keeping them out, their integration was followed by post-accession conditionality, the same model that should also be considered for current candidate countries.

“Enlargement is an exclusively European affair”

As much as we might like to see enlargement in this way, this has never been the case. In fact, over several previous decades, enlargement has become a mainly Euro-Atlantic affair. This has never been more pronounced than right now when the fate of Eastern enlargement waits to be resolved on the Ukrainian battlefield.

The growing calls for contingency plans in the case of Trump’s re-election and the diminishing American support testify to the extent of enlargement decided by EU member states. However, little is said about the American role in the Western Balkans. Here, too, as much as Europeans would not like to admit it, American support has become decisive in recent years. For example, diplomatic pressures from Washington have been tempering the mood of the Kosovar Prime Minister amid escalating tensions with Serbia.

Moreover, American support has not been limited to acting as the gendarme of the region, for it has also come with constructive solutions, amongst which the Open Balkans project is currently one of the most ambitious in the region.

The initiative involves Serbia, Albania, and North Macedonia, with Montenegro possibly joining in the near future. It pushes for the region’s greater integration with the EU. It paves the way for changes like no passports and tariffs for certain goods and promises to make another step towards EU integration.

In preparation for a possibly radical shift in Washington’s policies this Fall, Europeans should not only make contingency plans for Ukraine but for the Western Balkans as well.

A vicious circle that was once broken

“We must be prepared” goes the enlargement mantra. Despite some progress, so they say, candidate countries are not yet ready to join the Union because of their institutions, insufficient reforms, and social cohesion.

To put it in EU jargon, the Council of the European Union “highlighted the extent of the efforts which still have to be made in certain areas by the candidate countries to prepare for accession,” or “none of these countries fully satisfies all of the Copenhagen criteria at the present time.”

Does this statement justify the need for a pre-enlargement review in early 2025? In fact, the quote comes from March 1998, in relation to the accession prospects of countries which eventually joined the EU in 2004 – Lithuania, Czechia and Slovenia to name but a few.

We often think that previous accession waves went smoothly and that this time, it’s different. We tend to think that candidate countries pretend to reform while the EU pretends to be willing to accept them.

Ironically, the same sentiment was shared in 2001, when “Poland [was] pretending to prepare for membership and the EU [was] pretending to want it as a member.” So much for the novelty, at least in the context of Western Balkans, that the EU is facing in current accession talks.

However, even in relation to Eastern enlargement, where an ultimate outcome will be decided on the Ukrainian battlefield, much of the accession discussion is clouded by the same old prejudices.

We have seen these problems before, and many countries have still successfully integrated into the EU. It looks much more like the talk in EU capitals is about inventing reasons not to enlarge rather than to prepare for the expansion of a Europe that is whole and free.

*** Disclaimer/About: Over the last year, together with politicians and policy leaders, Visegrad Insight — Res Publica Foundation together with ZEIT STIFTUNG BUCERIUS developed four scenarios in a foresight report, which can be read here.

_

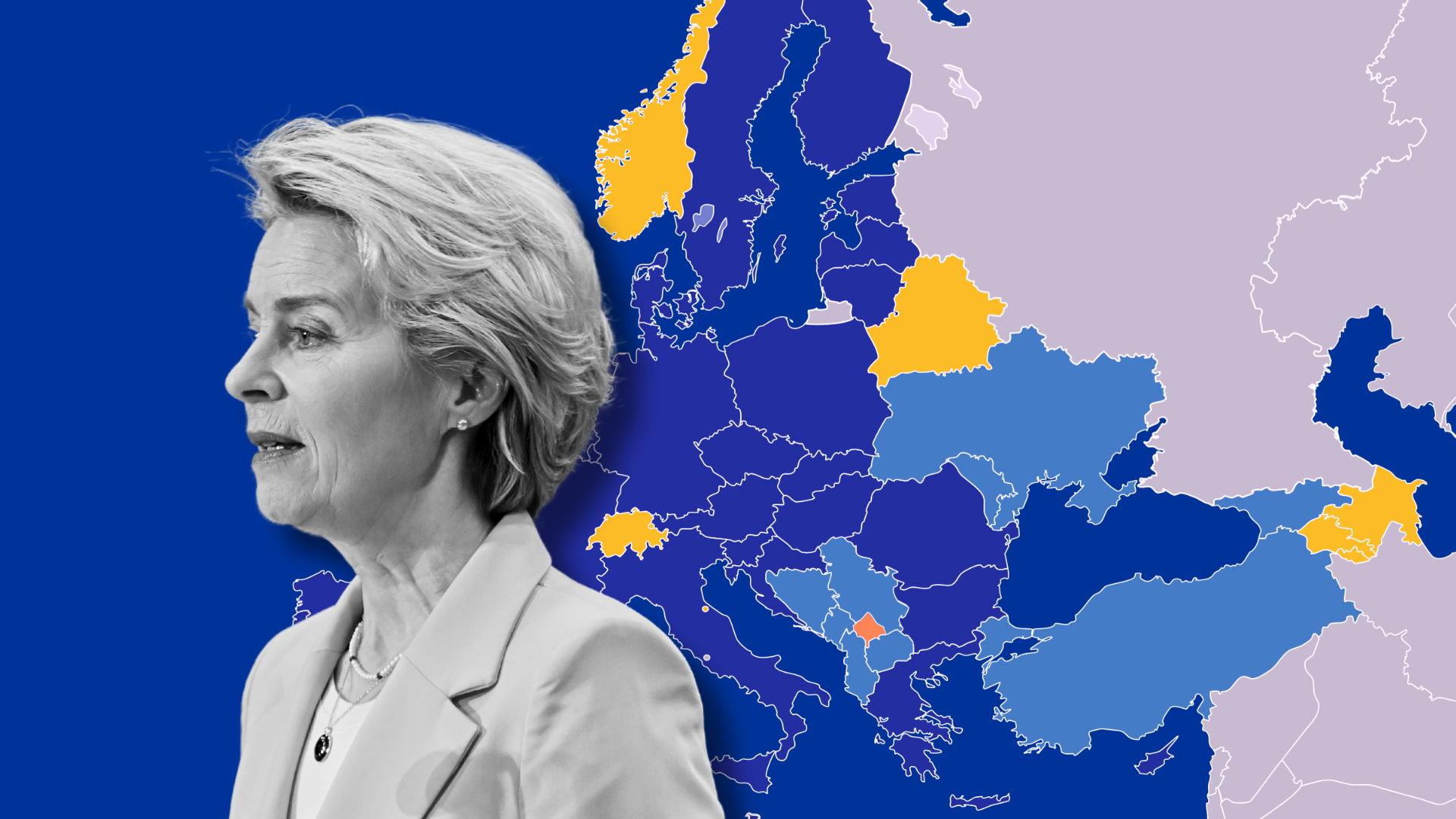

The featured image uses “Ursula von der Leyen presents her vision” (CC BY 2.0) by European Parliament.

Your Central European Intelligence

Democratic security comes at a price. What is yours?

Subscribe now for full access to expert analysis and policy debate on Central Europe.

The original article: belongs to Visegrad Insight .